DENTON, Texas — When talking about the early days of professional football, names like Johnny Unitas, Paul Hornung or Sam Huff, heroes of the National Football League, often come to mind.

Abner Haynes, a running back in the upstart American Football League, is one name not often mentioned. However, his story tells a narrative that reaches far beyond the gridiron.

In the years he played professional football for the AFL, 1960 to 1967, few played the game better than Abner Haynes.

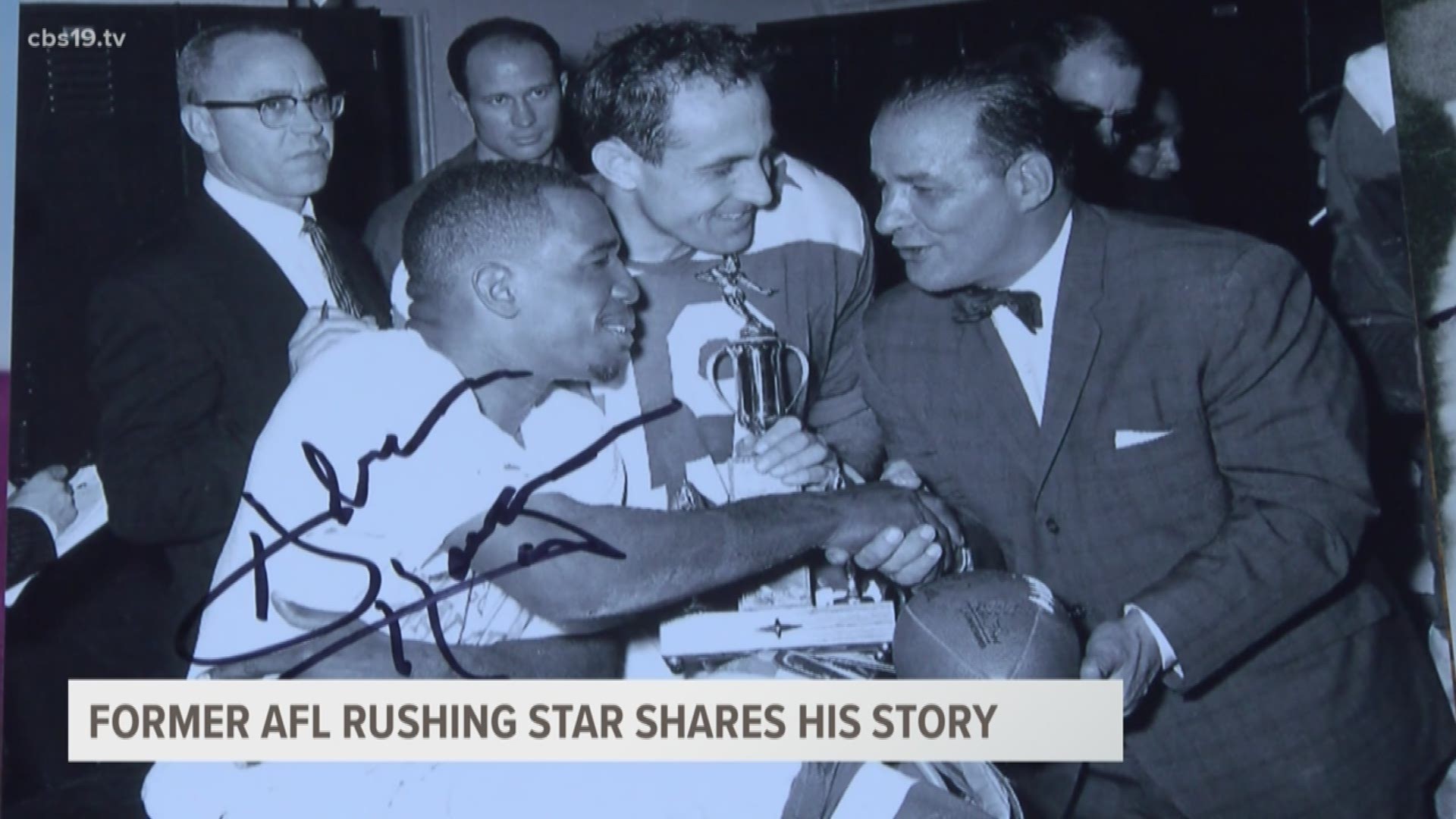

He was the league's Rookie of the Year and MVP in his very first season. He led the Dallas Texans to the 1962 championship. He was a four-time AFL all-star, three-time 1st team All-AFL and the 1964 Comeback Player of the Year.

Haynes racked up more than 4,600 yards as a running back and 3,500 as a receiver. In all, he scored 68 touchdowns as a back, receiver and kick returner.

Yet, these are merely numbers recorded in the history books.

Abner Haynes was born in 1937 in Denton. The youngest of nine children, it was a family-effort to keep the boy out of trouble early.

"My dad kept telling me, 'Man, use your brain instead of your anger,'" Haynes remembered. "It worked."

One passion the whole family shared was football.

"All of my brothers played high school ball. There was a ball around the house every day. Even my sisters could catch and would play ball with us, like the boys," Haynes remembered. "I lived across the street from the black city park. And we played everyday. I liked it. I liked to run. I liked the toughness of it. It was something we could do in the front yard, in the street. We played ball in the street. Wasn't much else you could do, other than go to church."

Church life was at the center of the Haynes family. His father was a minister who stressed education as a centerpiece of the household.

A talented recruit coming out of Lincoln High School, Haynes decided to continue his football career at what was then-known as North Texas State College in 1957 under legendary head coach Odus Mitchell. It was unprecedented in the state of Texas.

"My older brother came and told my parents that North Texas was talking about integrating," Haynes said. "Next thing I know, I gotta letter from North Texas telling me when to come to practice and where to come."

After talking with Coach Mitchell, it was not his race that was in question, but his size.

[My brother] went back and told my parents, 'Well they said they take, but said he's kinda little.' And they told him, 'Yeah, but he's tough,'" Haynes recalled.

Only three years after Brown v. Board, Haynes and his teammate Leon King became the first black men to play on an integrated college football team in Texas. It would be another decade before most of the big schools in the South would desegregate.

However, like his upbringing, he had a community to support him. In this case, it was his teammates.

"Will you block, will you tackle? Can you run, can you catch? And that becomes more important than what color you are. We didn't know that before we played football," Haynes said. "[We were] just straight guys. But when we start playing football together, we become a family."

Playing for an integrated football team in 1950's Texas was not without its problems. Opposing fans would boo and taunt him mercilessly. In addition to this, fights would break out on the field, simply because North Texas fielded a black man.

"Everywhere we would go play, especially my freshman year at North Texas, they would create problems with me being there," Haynes recalled. [My teammates] would be the ones to step up and make sure I was alright, surround me and help me walk off the field. I couldn't help but notice that these cats looking [were] out for me."

North Texas went undefeated (5-0) in his first year, which he attributes to the entire school coming together over the issue of race.

"It was something about winning that pulled that university together," Haynes said. "When we went undefeated, the whole town came together, to me. That's the way it looked to me. And they started recruiting more blacks."

North Texas would have two more successful years with Haynes, going 7-2-1 in 1958 and 9-2 in 1959. That last year, Haynes helped lead North Texas to No. 16 in the Associated Press Top 25 and a birth in the Sun Bowl.

Haynes impressed professional scouts and was selected in that year's NFL Draft.

"This is funny, I was drafted by Minnesota," Haynes said. "And about two hours later the phone rang again and it's the Oakland Raiders telling me we've traded for you. You are now an Oakland Raider."

At the same time, he was courted by representatives of the newly founded American Football League. The league, created by Lamar Hunt, had recently announced it would be integrated from the start.

"By the time I got home that evening, Lamar Hunt had called from the Dallas Texans. They had decided to integrate the new American League," Haynes said. "And I was being selected by Dallas. They had gotten me away from Oakland."

Relieved to be playing close to be home, Haynes became one of the AFL's first superstars. In his first season with the Texans, he led the league with 975 yards rushing, scored 12 total touchdowns and won the league's MVP and Rookie of the Year awards.

"I was what you call a breakaway runner. If you didn't watch yourself I would be gone," Haynes remembered. "I guess I was a pretty good runner. I liked the hitting, and I wasn't scared."

In 1962, the Texans won the AFL Championship. Though they were celebrating the victory, the team felt uneasy about competing for fans against the already established Dallas Cowboys.

After three years in Dallas, the team announced they would move to Kansas City to become the Chiefs.

"Dallas didn't need two pro football teams," Haynes said. "They just decided that Kansas City don't have a team. Let's take Dallas to Kansas City and become the Kansas City Chiefs. We packed up, drove up to Kansas City. I enjoyed the drive, upbeat."

To Haynes, while he did not have the same success as he did in Dallas, Kansas City was the glory days.

"We were just happy that the new league had worked. It had integrated. It was working. Kansas City was accepting of all the players," Haynes said. "It was fun. And it just kept increas[ing.]"

In 1965, Haynes was selected to play in the All-Star game in New Orleans, which was still largely segregated at the time. He was not allowed to check-in at the hotel and was called racial epithets. He, along with other players, called a meeting to discuss what to do next.

"We approached the coaches. I approached the general manager and told him what was going on. They didn't like it. We decided we weren't going to play in a city that treated us like that," Haynes explained. "We decided we were going to go to Houston to play the game."

The players helped to move the game to Houston from New Orleans and helped to further integrate sports in major cities around the country.

Following the 1964 season, Haynes was traded to the Denver Broncos. After two seasons, he finished his career with the Miami Dolphins and later that season with the New York Jets.

After the 1967 season, Abner Haynes, one of the great stars of the AFL, announced his retirement. Two years later, the New York Jets, led by Haynes' old roommate Joe Namath, beat the Baltimore Colts in Super III, remembered as one of the greatest upsets in professional football history. Shortly thereafter, the two leagues completed their merger into the NFL. With the foundation laid by players like Abner Haynes, the AFL experiment was a success.

Haynes would go on to many other ventures in life. However, the 82-year-old continues his interest in football and the role it plays in American society.

He says while he believes the NFL's future is bright, he would like to see the league to open up to more black ownership.

"I understand the situation but there's nothing too hard for us to address," Haynes explained. "I'm looking forward to that. I don't know if I'll see it but I'm looking forward to the humans feeling like everyone is welcome at the table."

He remains a Kansas City fan. With Patrick Mahomes at the helm, he believes the team has plenty of promise ahead.

"I think it's great that he will have the opportunity to expand that position," Abner said. "Football is a game that's been played a long time, things have been learned and improved on."

Abner still lives in Texas, not far from where he grew up and established his reputation as a fierce player on-the-field and a trailblazer off of it. His number 28 was retired by both North Texas and Kansas City.

More important than legacy, however, he hopes his story serves as an example of the power of integration and how it makes the world a better place.

"My white brothers stuck with me the same way my black brothers stuck with me," Haynes said. "It's fellowship. It's brotherhood."