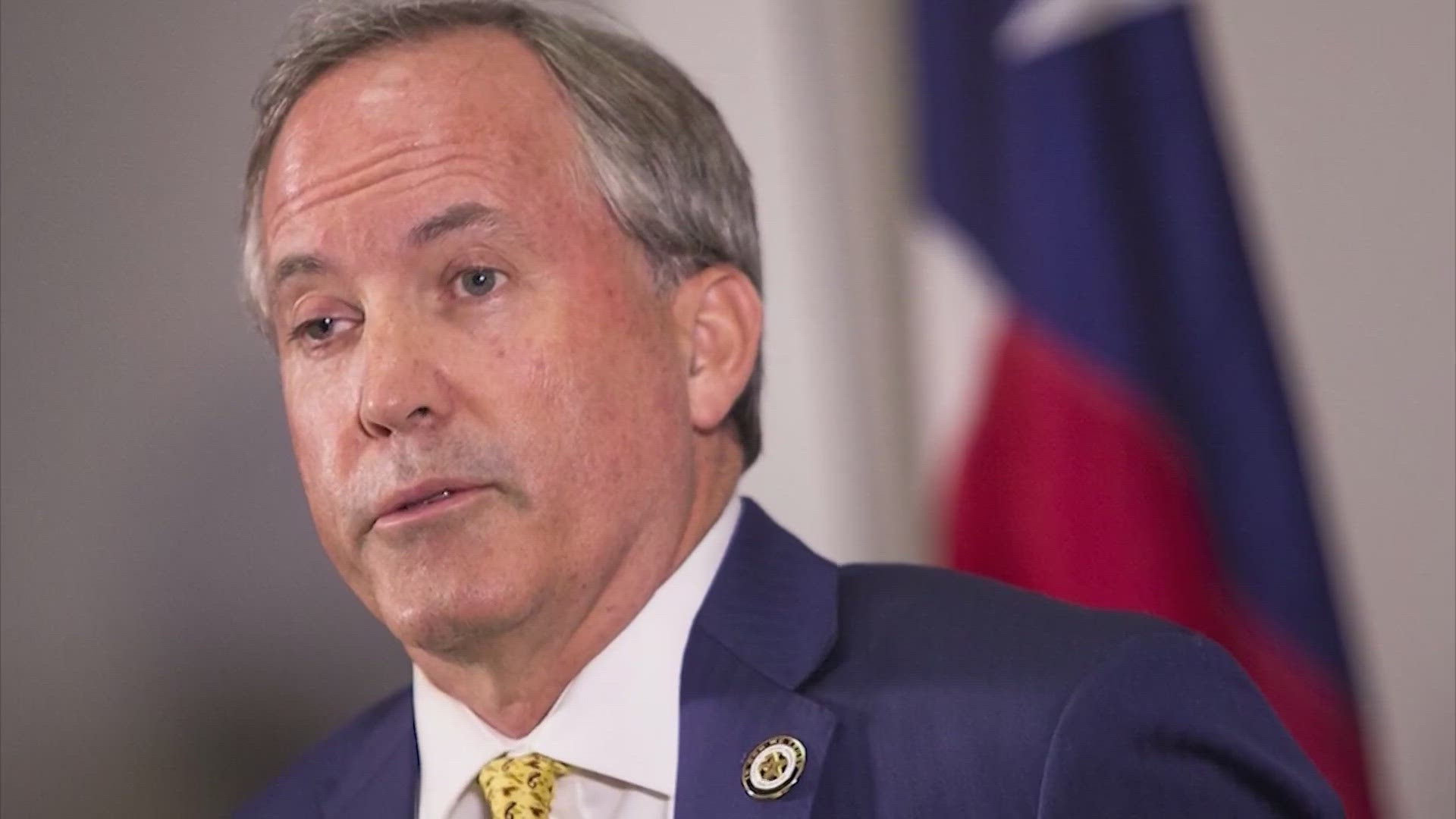

AUSTIN, Texas — Texas’ GOP-led House of Representatives impeached state Attorney General Ken Paxton on Saturday on articles including bribery and abuse of public trust, a sudden, historic rebuke of a fellow Republican who rose to be a star of the conservative legal movement despite years of scandal and alleged crimes.

The vote triggers Paxton’s immediate suspension from office pending the outcome of a trial in the state Senate and empowers Republican Gov. Greg Abbott to appoint someone else as Texas’ top lawyer in the interim.

The 121-23 vote constitutes an abrupt downfall for one of the GOP’s most prominent legal combatants, who in 2020 asked the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn President Joe Biden’s electoral defeat of Donald Trump. It makes Paxton only the third sitting official in Texas’ nearly 200-year history to have been impeached.

Here's how the members of the House voted:

RELATED: How Houston-area House members voted

WHO THEY ARE: Read the bios of the members of the House investigative committee, including Rep. Ann Johnson from Houston.

Paxton, 60, decried the move moments after scores of his fellow partisans voted for impeachment, and his office pointed to internal reports that found no wrongdoing.

“The ugly spectacle in the Texas House today confirmed the outrageous impeachment plot against me was never meant to be fair or just,” Paxton said. "It was a politically motivated sham from the beginning,”

Paxton has been under FBI investigation for years over accusations that he used his office to help a donor and was separately indicted on securities fraud charges in 2015, though he has yet to stand trial. His party had long taken a muted stance on the allegations — but that changed this week as 60 Republicans, including House Speaker Dade Phelan, voted to impeach.

“No one person should be above the law, least not the top law t officer of the state of Texas,” Rep. David Spiller, a Republican member of the committee that investigated Paxton, said in opening statements. Another Republican committee member, Rep. Charlie Geren, said without elaborating that Paxton had called some lawmakers before the vote and threatened them with political “consequences.”

Lawmakers allied with Paxton tried to discredit the investigation by noting that hired investigators, not panel members, interviewed witnesses. They also said several of the investigators had voted in Democratic primaries, tainting the impeachment, and that they had too little time to review evidence.

“I perceive it could be political weaponization,” Rep. Tony Tinderholt, one of the House’s most conservative members, said before the vote. Republican Rep. John Smithee compared the proceeding to "a Saturday mob out for an afternoon lynching.”

Paxton is automatically suspended from office pending the Senate trial. Final removal would require a two-thirds vote in the Senate, where Paxton’s wife’s, Angela, is a member.

Representatives of the governor, who lauded Paxton while swearing him in for a third term in January, did not immediately respond to requests for comment on a temporary replacement.

Before the vote Saturday, Trump and U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz came to Paxton's defense, with the senator calling the impeachment process “a travesty” and saying the attorney general’s legal troubles should be left to the courts.

“Free Ken Paxton,” Trump wrote on his social media platform Truth Social, warning that if House Republicans proceeded with impeachment, “I will fight you.”

In one sense, Paxton’s political peril arrived with dizzying speed: The House committee's investigation came to light Tuesday, and by Thursday lawmakers issued 20 articles of impeachment.

But to Paxton’s detractors, the rebuke was years overdue.

In 2014, he admitted to violating Texas securities law, and a year later he was indicted on securities fraud charges in his hometown near Dallas, accused of defrauding investors in a tech startup. He pleaded not guilty to two felony counts carrying a potential sentence of five to 99 years.

He opened a legal defense fund and accepted $100,000 from an executive whose company was under investigation by Paxton’s office for Medicaid fraud. An additional $50,000 was donated by an Arizona retiree whose son Paxton later hired to a high-ranking job but was soon fired after displaying child pornography in a meeting. In 2020, Paxton intervened in a Colorado mountain community where a Texas donor and college classmate faced removal from his lakeside home under coronavirus orders.

But what ultimately unleased the impeachment push was Paxton's relationship with Austin real estate developer Nate Paul.

In 2020, eight top aides told the FBI they were concerned Paxton was misusing his office to help Paul over the developer's unproven claims that an elaborate conspiracy to steal $200 million of his properties was afoot. The FBI searched Paul’s home in 2019, but he has not been charged and denies wrongdoing. Paxton also told staff members he had an affair with a woman who, it later emerged, worked for Paul.

The impeachment accuses Paxton of attempting to interfere in foreclosure lawsuits and issuing legal opinions to benefit Paul. Its bribery charges allege that Paul employed the woman with whom Paxton had an affair in exchange for legal help and that he paid for expensive renovations to the attorney general's home.

A senior lawyer for Paxton’s office, Chris Hilton, said Friday that the attorney general paid for all repairs and renovations.

Other charges, including lying to investigators, date back to Paxton’s still-pending securities fraud indictment.

Four of the aides who reported Paxton to the FBI later sued under Texas’ whistleblower law, and in February he agreed to settle the case for $3.3 million. The House committee said it was Paxton seeking legislative approval for the payout that sparked their probe.

“But for Paxton’s own request for a taxpayer-funded settlement over his wrongful conduct, Paxton would not be facing impeachment,” the panel said.

These are the 20 articles of impeachment filed against Paxton

THE PROCESS

Under the Texas constitution and law, impeaching a state official is similar to the process on the federal level: the action starts in the state House.

In this case, the five-member House General Investigating Committee voted unanimously Thursday to send 20 articles of impeachment to the full chamber. The next step is a vote by the 149-member House, where a simple majority is needed to approve the articles. Republicans control the chamber 85-64.

The House can call witnesses to testify, but the investigating committee already did that prior to recommending impeachment. The panel met for several hours Wednesday, listening to investigators deliver an extraordinary public airing of Paxton’s years of scandal and alleged lawbreaking.

If the full House impeaches Paxton, everything shifts to the state Senate for a “trial” to decide whether to permanently remove Paxton from office, or acquit him. Removal requires a two-thirds majority vote.

A SUDDEN THREAT

But there is a major difference between Texas and the federal system: If the House votes to impeach, Paxton is immediately suspended from office until the outcome of the Senate trial. Republican Gov. Greg Abbott would have the opportunity to appoint an interim replacement.

The GOP in Texas controls every branch of state government. Republican lawmakers and leaders alike have until this week taken a muted posture toward the myriad examples of Paxton’s misconduct and alleged lawbreaking that emerged in legal filings and news reports over the years.

It’s unclear when and why exactly that changed.

In February, Paxton agreed to settle a whistleblower lawsuit brought by former aides who accused him of corruption. The $3.3 million payout must be approved by the House and Republican Speaker Dade Phelan has said he doesn’t think taxpayers should foot the bill.

Shortly after the settlement was reached, the House investigation into Paxton began.

REPUBLICAN ON REPUBLICAN

The five-member committee that mounted the investigation of Paxton is led by his fellow Republicans, contrasting America’s most prominent recent examples of impeachment.

Trump's federal impeachments in 2020 and 2021 were driven by Democrats who had majority control of the U.S. House of Representatives. In both cases, the impeachment charges approved by the House failed in the Senate, where Republicans had enough votes to block the conviction.

In Texas, Republicans control both houses by large majorities and the state’s GOP leaders hold all levers of influence. But that hasn’t stopped Paxton from seeking to rally a partisan defense.

When the House investigation emerged Tuesday, Paxton suggested it was a political attack by Phelan. He called for the “liberal” speaker’s resignation and accused him of being drunk during a marathon session last Friday.

Phelan’s office brushed off the accusation as Paxton attempting to “save face.” None of the state’s other top Republicans have voiced support for Paxton since.

Paxton issued a statement Thursday, portraying impeachment proceedings as an effort to disenfranchise the voters who gave him a third term in November. He said that by moving against him “the RINOs in the Texas Legislature are now on the same side as Joe Biden.”

THE MARRIAGE WRINKLE

But Paxton, who served five terms in the House and one in the Senate before becoming attorney general, is sure to still have allies in Austin.

A likely one is his wife, Angela, a two-term state senator who could be in the awkward position of voting on her husband’s political future. It’s unclear whether she would or should participate in the Senate trial, where the 31 members make margins tight.

In a twist, Paxton’s impeachment deals with an extramarital affair he acknowledged to members of his staff years earlier. The impeachment charges include bribery for one of Paxton’s donors, Austin real estate developer Nate Paul, allegedly employing the woman with whom he had the affair in exchange for legal help.

YEARS IN THE MAKING

The impeachment reaches back to 2015, when Paxton was indicted on securities fraud charges for which he still has not stood trial. The lawmakers charged Paxton with making false statements to state securities regulators.

But most of the articles stem from Paxton’s connections to Paul and a remarkable revolt by the attorney general’s top deputies in 2020.

That fall, eight senior Paxton aides reported their boss to the FBI, accusing him of bribery and abusing his office to help Paul. Four of them later brought the whistleblower lawsuit. The report prompted a federal criminal investigation that in February was taken over by the U.S. Justice Department’s Washington-based Public Integrity Section.

The impeachment charges cover myriad accusations related to Paxton’s dealings with Paul. The allegations include attempts to interfere in foreclosure lawsuits and improperly issuing legal opinions to benefit Paul, and firing, harassing and interfering with staff who reported what was going on. The bribery charges stem from the affair, as well as Paul allegedly paying for expensive renovations to Paxton’s Austin home.

The fracas took a toll on the Texas attorney general’s office, long one of the primary legal challengers to Democratic administrations in the White House.

In the years since Paxton’s staff went to the FBI, his agency has come unmoored by disarray behind the scenes, with seasoned lawyers quitting over practices they say aim to slant legal work, reward loyalists and drum out dissent.

TEXAS HISTORY

Paxton was already likely to be noted in history books for his unprecedented request that the U.S. Supreme Court overturn Joe Biden’s defeat of Trump in the 2020 presidential election. He may now make history in another way.

Only twice has the Texas House impeached a sitting official.

Gov. James “Pa” Ferguson was removed from office in 1917 for misapplication of public funds, embezzlement and the diversion of a special fund. State Judge O.P. Carrillo was forced out of office in 1975 for using public money and equipment for his own use and filing false financial statements.