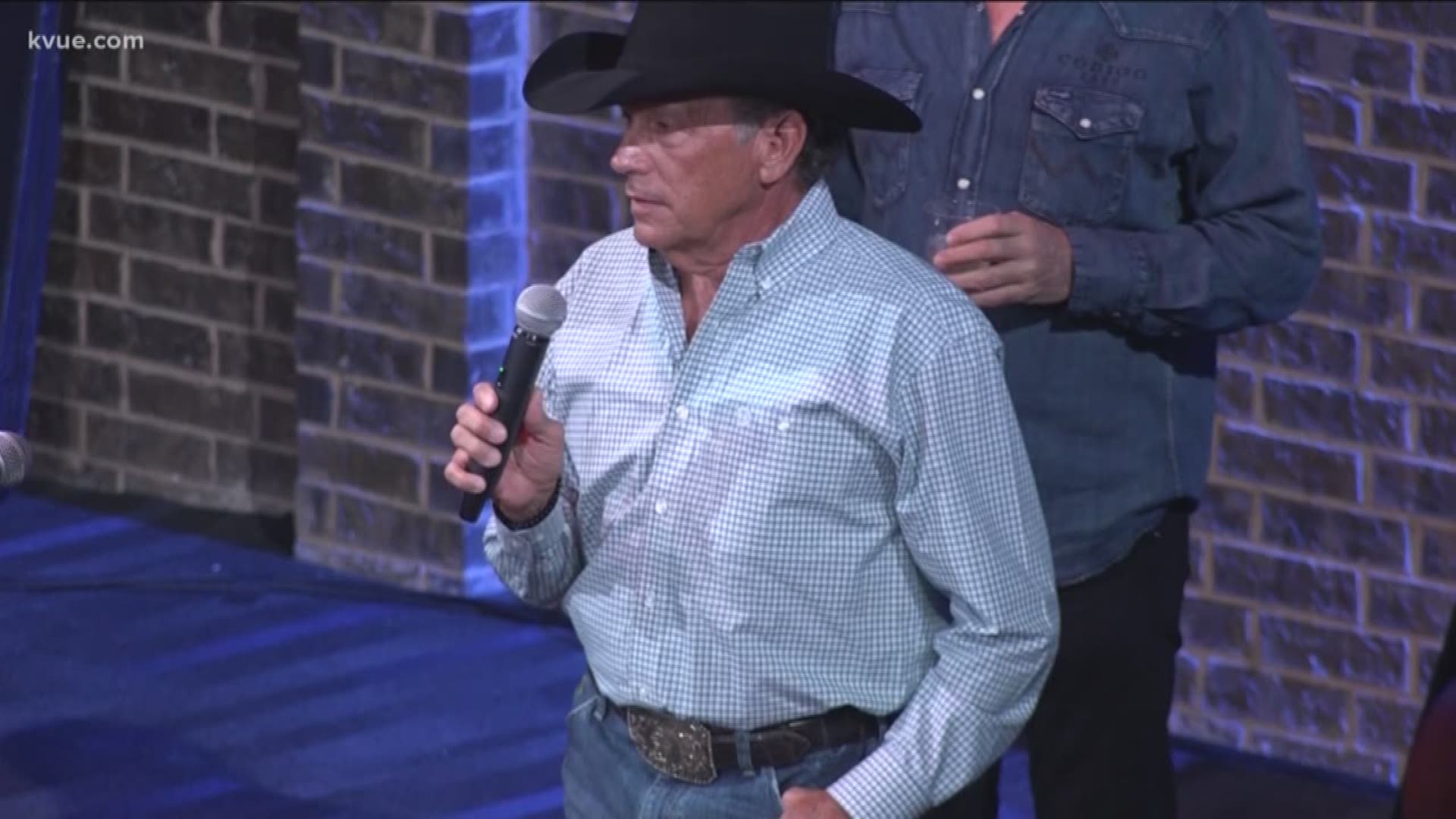

THE TEXAS TRIBUNE – To celebrate Gov. Greg Abbott’s reelection last year, his inaugural committee paid a whopping $1.7 million to hire country crooner George Strait and his band. A coterie of top political aides and staff got more than $1 million, some of it paid out in six-figure bonuses. And a handful of lucky charities received $800,000 in unspent money.

Left out of that tally: the $116,000 taxpayers spent to keep all those inaugural expenditures secret.

Abbott and the 2019 Texas Inaugural Committee spent months fighting the disclosure of documents detailing how they spent a record-setting $5.3 million that event organizers raised mostly from corporations and wealthy donors.

But The Texas Tribune sued the committee under the Texas Public Information Act and earlier this year successfully obtained the bank statements and spending ledger in an out-of-court settlement.

The result is the most detailed and complete account of inaugural spending in decades. Austin attorney Bill Aleshire, who represented the Tribune in the lawsuit, said the legal fight he had to wage to get the records highlights the need for better transparency in state inaugurations, which suck up gobs of corporate money but face little regulation over how it gets spent.

“We just don't have that level of transparency written into the law,” Aleshire said.

Newly obtained financial records offer a more detailed breakdown of how the Texas Inaugural Committee spent the money it raised for the inauguration of Gov. Greg Abbott and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick. More than $1 million was paid to top political aides and staff, including about $908,000 in fundraising commissions and $850,000 in wages.

Few records document inaugural committee spending in the state, and those that exist are inconsistent about how expenditures are categorized year to year.

But available documents dating to the late 1970s show spending on Abbott’s two inaugurals has eclipsed that of any other in Texas for at least 40 years; inaugural committee spending has soared from $1.6 million in 1983 to $5.6 million in 2015, with both figures adjusted for inflation.

The newly obtained financial records show that an increasing share of the money has gone to “professional fees,” payroll for political staff and fundraisers — some of whom earned six-figure payments from the event last year.

In 2019, the committee spent $1.9 million, or 35% of the money from donors and ticket sales, on those personnel costs, after spending 27% on them in 2015.

By contrast, 5.7% of the money spent on the 1983 inaugural went to contractors and payroll. That rose to 10.6% in 1991, 14% in 1995 and averaged 18% under former Gov. Rick Perry. (The financial report for 1999, covering former Gov. George W. Bush’s second inaugural, could not be located by the Tribune.)

Experts said the amount spent on fundraising in 2019 far exceeded the norm. Usually fundraisers can expect to receive about 10% on what they raise for a political campaign. Instead, the inaugural committee spent nearly twice that — 19% — on fundraising last year.

Unlike raising money for a campaign, where direct corporate contributions are banned and the candidates haven’t been elected yet, the inaugural fundraisers had the relatively easy task of asking people and companies to write checks for the winners, said Mark Jones, a political scientist at Rice University. Big donations also bought entrée to special events, like a candlelight dinner or a photo opportunity with the governor.

“That’s a check that pretty much writes itself,” Jones said, adding that given the ease of raising money for the guaranteed winners, one might expect paying nothing more than “a small processing fee.”

“I'd probably view it, more than anything else, as a combination of waste and extravagance,” Jones said. “They seem to be needlessly rewarding people for whom it's not entirely clear why they merit being rewarded at that level.”

Abbott’s office did not respond to a detailed request for comment. Nor did Kimberly Snyder, Abbott’s 2018 campaign director and the executive director of his 2019 inaugural committee.

The Texas Inaugural Committee is typically chaired by politically connected donors — last year, the chairs and co-chairs were banker and Texas Transportation Commission Chair J. Bruce Bugg Jr., businessman Ray Hunt and philanthropist Mindy Hildebrand.

But in practice it is controlled by the governor, who not only picks the entertainment but also puts political confidants and consultants in key positions and exercises broad power over all financial decisions. The lieutenant governor, though given one of three committee appointments, by all accounts plays something like third fiddle during inaugurations.

The fundraisers got just under $1 million in commissions alone — with more than $700,000 of that going to Abbott Campaign Finance Director Sarah Whitley and deputy Sydney Wallace. Neither responded to emailed requests for comment.

Whitley, the committee’s top earner, made $539,865 in just four months — including a $200,000 bonus. Add in the $416,116 Whitley made from Abbott’s campaign in 2019, and her earnings shot up to $955,981 last year, the records show.

Wallace got $188,000 from the inaugural committee, $100,000 of that a bonus. Combined with what she earned from Abbott’s campaign, she made $434,622 in 2019.

By contrast, two fundraisers for Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick — Blakemore & Associates and Fundraising Solutions — were paid a combined $100,000 and raised $1 million, about a fifth of the total haul, a Patrick adviser told the Tribune last year. They received the standard 10% commission, half what Abbott’s fundraisers got. (Two other fundraisers, Meg Gazzini and Lindsay Sheeder Brown, each made $40,000 from fundraising commissions.)

Patrick’s office did not respond to a recent request for comment.

The inaugural committee was lucrative for other Abbott aides — like Snyder, his 2018 campaign director and the second-highest paid staffer. She earned $277,474 in salary from the inaugural committee.

In all, the committee spent $898,865 on payroll, $30,832 on legal and professional fees, $907,865 on fundraising commissions and $6,330 on fundraisers’ travel and meals, inaugural records show.

Those administrative costs were more than six times higher than what the committee spent on the inaugural barbecue ($270,956), an event that was open to the public and included a face-painter ($1,200) and a petting zoo ($1,550).

Elsewhere, the committee purchased $7,305 worth of flowers, spent $7,150 on gifts, $450 for “makeup services” and $469 for “photos for Dan Patrick.”

The only category of expense that rivaled the administrative spending was the just under $1.9 million for the inaugural ball. Nearly all of that went to AEG Presents, the live music production and promotion company that sponsors George Strait, who headlined the event.

AEG affiliate Messina Touring Group, a Strait tour promoter, got $175,000 of that total and two companies representing country singer Aaron Watson received $75,000. Event planners also spent $194 on towels for “GS/Band,” presumably Strait and his band, in what appeared to be a last-minute jaunt to four different Walmarts the day before the inaugural ball on Jan. 15.

Past inaugural balls have featured entertainers ranging from Texas country performers Robert Earl Keen and Clay Walker (Perry), the Dixie Chicks (Bush) and Tejano singer "Little" Joe Hernandez (Ann Richards).

But taken alone, the cost for Strait and Watson surpassed the total amount Abbott’s predecessors spent on their whole inaugural balls for at least 40 years, even when adjusted for inflation.

The inaugural committee pulled in so much money it didn’t spend it all on events, so 31 charities received a combined $800,000 in donations, including a foundation named for late Iraq War veteran Chris Kyle of “American Sniper” fame.

Abbott’s office had declined repeated requests to name the charities that benefited from the leftover inaugural cash, but the ledgers obtained from the lawsuit settlement show the charities included nonprofits that advocate for abused and neglected children and chapters of Meals on Wheels, where the first lady and governor have volunteered.

While some of the charities had long-standing relationships with the first lady, others said they were surprised by the donations. Several chapters of CASA — Court Appointed Special Advocates — were invited to the Governor’s Mansion for a tea in June 2019, where they posed for photos with Cecilia Abbott, toured the mansion and dined at a table set with formal gold-rimmed dishes and pink and white bouquets.

“It was like, ‘Oh my God, pinch me,’” said Veronica Whitacre, executive director of the CASA in Hidalgo County, who said she was “honored and thrilled” to have been selected.

The largest donation, of $250,000, went to the Texas VFW Foundation, for the publication of a book commemorating the Vietnam War, said Beth Creasey, manager of the foundation. More than 15,000 copies of the book have been distributed to veterans and their families, as part of an effort to recognize the veterans and encourage them to apply for government benefits, according to Elaine Zavala, a spokesperson for the Texas Veterans Commission, which worked on the book.

The revelations in the records come after a monthslong court fight which began last year when the Tribune asked the inaugural committee to provide its spending records under public information laws. The Tribune also asked the Texas Secretary of State’s office not to dissolve the state-created committee until the documents were released.

Instead, Snyder claimed they had “no responsive records.” The Tribune sued, and Secretary of State Ruth Hughs dissolved the committee soon after.

Five days after that, a process server tried to deliver the lawsuit to Bugg, the chair of the inaugural committee. His wife said he was in the shower, and that there was “never a good time” to serve him, according to the server’s notes.

Texas Department of Transportation spokesman Bob Kaufman, responding on behalf of Bugg, noted that the attorney general’s office “promptly reached out and arranged to accept” the paperwork. Spokespeople for the attorney general’s office and the secretary of state’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

A month later, the attorney general’s office — which defends state agencies and officials in court — sought to toss the lawsuit. The rationale: Hughs had dissolved the committee, making it a “nonexistent entity” that had “no capacity to be sued.”

Aleshire, the Tribune’s lawyer, called those “shenanigans” highly unusual.

“It was particularly suspicious and anti-transparency for them to dissolve the agency — disappear the committee — before they responded to the public information request, and then try to undermine [the] lawsuit as a result of that tactic,” said Aleshire, who focuses on government transparency issues.

Ultimately, the attorney general’s office offered to provide the inaugural committee’s bank statements and accounting ledgers if the Tribune agreed to drop its lawsuit. According to a tally of the costs associated with the case, mostly hourly salaries and overhead, the attorney general’s office spent $115,998 trying to keep the records secret.

Aleshire said there’s no reason why the Texas Inaugural Committee should be walled off from scrutiny.

“Without transparency, you’re left with the worst of both worlds: unfair and unjustified suspicion and accusations against government officials,” he said. “On the other side, a complete absence of the information needed to know whether or not those suspicions are true.”

Carla Astudillo, Darla Cameron and Houston Chronicle Data Editor Matt Dempsey contributed to this report.

Disclosure: Rice University, the Texas Secretary of State's Office and the Texas Veterans Commission have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This story originally appeared in The Texas Tribune.

The Texas Tribune mission statement:

The Texas Tribune is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: