The Fowl Neighbor Next Door: East Texans fought back and won when a chicken farm – and its smells – moved in

A judge closed it. Now, the Texas Supreme Court has been asked to decide if it should reopen in a case with statewide ramifications for landowners and homeowners.

Mersini Blanchard says the first clue a fowl neighbor had moved in was the foul smell.

She thought at first there was a dead animal nearby.

Blanchard and her neighbors would soon realize the smell was coming from a newly built chicken farm, just over a mile from her Malakoff home in Henderson County, about 70 miles southeast of Dallas.

“Sometimes it’s so bad … you cannot come outside to enjoy your property anymore,” Blanchard said.

Appraisal district and court records show the value of the family’s home and 1,200 acres of surrounding property plunged 75 percent after the chicken farm – and the smell – moved in.

“I was going to be stuck with a piece of property here that would basically be worthless,” said Mersini’s son, Frank Blanchard, a Dallas custom home builder.

Frustrated, the Blanchards and their neighbors banded together to file a nuisance lawsuit. They asked that the chicken farm operation be shut down.

In 2019, a jury sided with them, finding the farm was a nuisance to the neighbors. Henderson County District Judge Scott McKee ordered that the chicken farm operation be closed.

“Defendants deny a nuisance exists and have either taken no or insufficient measures to reduce the odor pollution...,” Judge McKee wrote.

Almost two years after the farm operation was shuttered, neighbors worry the smells could return. Sanderson Farms, which supplies chickens to the farm, has appealed the case.

Now before the Texas Supreme Court, any ruling will have potential ramifications for homeowners’ and landowners’ rights across the state.

In Sanderson Farms’ petition to the Texas Supreme Court, the company says the judge’s decision to close the farm operation is a “fundamental misfit for a temporary nuisance.”

The company argues that if the farm operation can’t reopen, it would be bad for business. “No rational investor will risk investing substantial resources knowing even a temporary problem can lead to permanent loss of the investment,” the filing says.

“Several lawsuits have already been filed against poultry farms across the state, and this decision provides a roadmap for shutting them down,” the filing says.

The company declined a request for comment, citing the ongoing litigation.

Neighbors and their attorneys argue that the district court’s ruling to close the farm should be upheld.

“If the neighbors in Henderson County were to lose, it would absolutely embolden Sanderson,” said Brian Lauten, an attorney representing the neighbors. “I think what you’ll see is a domino effect of barns popping up all over East Texas.”

Chapter 1 New farm moves in

The path that led to this Supreme Court case begins in 2015.

That’s the year Steve Huynh purchased about 230 acres in Malakoff to open a chicken farm for Sanderson Farms. He had operated other chicken farms for Sanderson Farms beginning in 2002.

Sanderson Farms approved Steve’s son, Timmy Huynh, as a grower, even though he was a college student in California and had no prior chicken farming experience, according to records and testimony.

Steve Huynh later acknowledged under oath that he filled out the paperwork and signed Timmy’s name on the contract with Sanderson Farms.

Sanderson Farms also approved Thinh Nguyen, Steve’s cousin, as a grower. He would later testify that he had no prior experience raising chickens. But testimony would show he was actually on site, unlike Timmy, who was out of state.

So, at least on paper, there were two farms – one 8-barn operation operated by Timmy Huynh and another operated by Nguyen – on the same property.

State records and court testimony would later show state officials were given incorrect or misleading information about how close neighbors would be to the operation, the size of the operation, and about the prevailing winds, which would later blow odors in the direction of neighboring homes.

Along the way, attorneys representing the neighbors uncovered financial and operational irregularities.

Testimony revealed Timmy Huynh did not sign the contract with Sanderson nor state and federal applications associated with the chicken farm.

Chapter 2 Federal subsidy

Steve Huynh testified that he had signed his son’s name on documents applying for a federal government subsidy intended to help socially disadvantaged farmers.

The contract, however, for the subsidy says: “the participant must have control of the land for the duration of the contract.”

Records show the federal government sent subsidies totaling about $160,000 in Timmy Huynh’s name.

The Huynhs and Nguyens did not respond to phone calls or letters from WFAA.

Sanderson supplied the first flock of chickens in June 2016. On that 16-barn site, each barn contained about 28,000 chickens, or more than 440,000 per flock.

By the fall, neighbors had begun noticing the smell.

“If you’ve run over roadkill before, and you have those few seconds of, ‘Oh, my gosh,’ that’s what it was like,” said Emily Martinez, a Malakoff teacher who lives with her two daughters and husband just over a half mile away. “Except… sometimes it would stay for hours.”

Chapter 3 Complaints mount

Neighbors complained to state environmental officials. Frank Blanchard met with elected officials.

In Oct. 2016, a state investigator wrote that the “source of the odors was determined to be the chicken houses.”

Steve Huynh, the operation’s owner, sent a letter to the state promising changes to “eliminate the odor.”

Neighbors, however, said the smell never got better.

Records show neighbors repeatedly reached out to Sanderson Farms officials complaining about the odor.

In March 2017, Blanchard spoke with Sanderson Farms division manager Randall Boehme. Blanchard recorded the call, which was played during the trial. Blanchard asked Boehme if he could expect to be stunk “out of his property” about every 11 weeks.

Boehme responded, “That’s our production cycle, yes, sir.”

Testimony showed Boehme was referring to the “catching” - the period at the end of a 60-day growing cycle when the grown birds are rounded up and taken to a processing plant. Smells are more intense during that time.

That same day, Blanchard received a call from Huynh.

“Your farm is stinking up my property all the time,” Blanchard told him, according to an audio recording of the call also used in the litigation. “So I was just wondering if you are gonna do something about it?”

Huynh responded that he was trying to “keep it down on the odors.”

“You’re destroying everybody’s quality of life, interfering with their property and destroying their property values,” Blanchard told Huynh.

Huynh responded that he had gained approval to build the chicken farms where they were located.

“I just do what the law say,” he said.

Around this time, neighbors learned about the Texas Right to Farm law. They discovered it set strict time constraints on the ability of neighbors to file suit – in this case, one year.

Chapter 4 Lawsuit filed

Neighbors filed suit in May 2017.

Sanderson Farms and its growers tried to have the lawsuit thrown out, claiming in a court filing that neighbor had missed the deadline.

But neighbors had made the deadline with one month to spare, records show. The lawsuit moved forward.

Blanchard and the other neighbors began keeping odor logs detailing when the smell intensified, and state investigators kept issuing notices of violation.

In August 2017, Thinh Nguyen sent a signed letter to state regulators contesting a notice of violation at his farm. The letter argued that “the chicken waste odor” should be classified as “merely unpleasant” rather than “offensive.”

Steve Huynh signed and sent in the same letter on behalf of the other farm, 300 feet away.

Those identical letters argued that neither farm could be held accountable for the odor “since it appears no effort was undertaken to identify which of these two poultry farms was the actual source of the alleged odors.”

Testimony showed the letters were prepared by Sanderson Farms officials.

State regulations also required that the farmers turn in a “strategic odor control plan” to environmental regulators after the farm had been issued three notices of violation.

Chapter 5 Odor control plan

Testimony showed, however, that it was Sanderson Farms that turned in the odor control plan to state regulators. But Sanderson Farms officials didn’t give the plan to the farm operators until months later, in March 2018.

Steve Huynh testified during his deposition that he did not know why he did not receive the odor control plan and did not ask Sanderson why there had been a delay.

A Purdue University poultry expert hired by the neighbors found the operation produced about 10 million pounds, or 5,000 tons, of manure every year. He also said the 16 chicken houses emitted 175 tons of ammonia annually, and 1,037 pounds of hydrogen sulfide, a rotten egg smell created by decomposing manure.

Testimony showed that as many as 5 percent of the chickens would die every flock, producing tens of thousands of pounds of decomposing carcasses.

The lawsuit also revealed how little training the farm’s operators had received.

In his deposition, Steve Huynh testified he had attended one class on how to control chicken odors that lasted a few hours. Nguyen testified that he had attended an afternoon class on odor control, and that he did not know what constituted a nuisance.

Chapter 6 A jury decides

The case went to trial in October 2019. By then, state environmental officials had issued 10 air quality notices of violations to the farmers.

In the final notice of violation, issued weeks before the trial, a state investigator wrote that he could “smell the odor inside the moving vehicle with the air conditioning on and the windows rolled up.”

Ed Chisholm, a top-ranking Sanderson Farms official, testified near the end of the trial. He told jurors, “there will be absolutely no change to anything with respect to how these chicken farms are operated.”

When asked about their contract farmers’ chicken-growing practices, Chisholm testified that the farmers had followed the company’s policies.

When the trial concluded after three weeks of testimony, ten of 12 jurors sided with the neighbors. While criminal trials require a unanimous jury to reach a verdict, civil trials only require five sixths, or 10 of 12 jurors, to agree on a verdict.

Jurors awarded the Blanchards $4.87 million. The rest of the neighbors were awarded a combined total of $1.11 million.

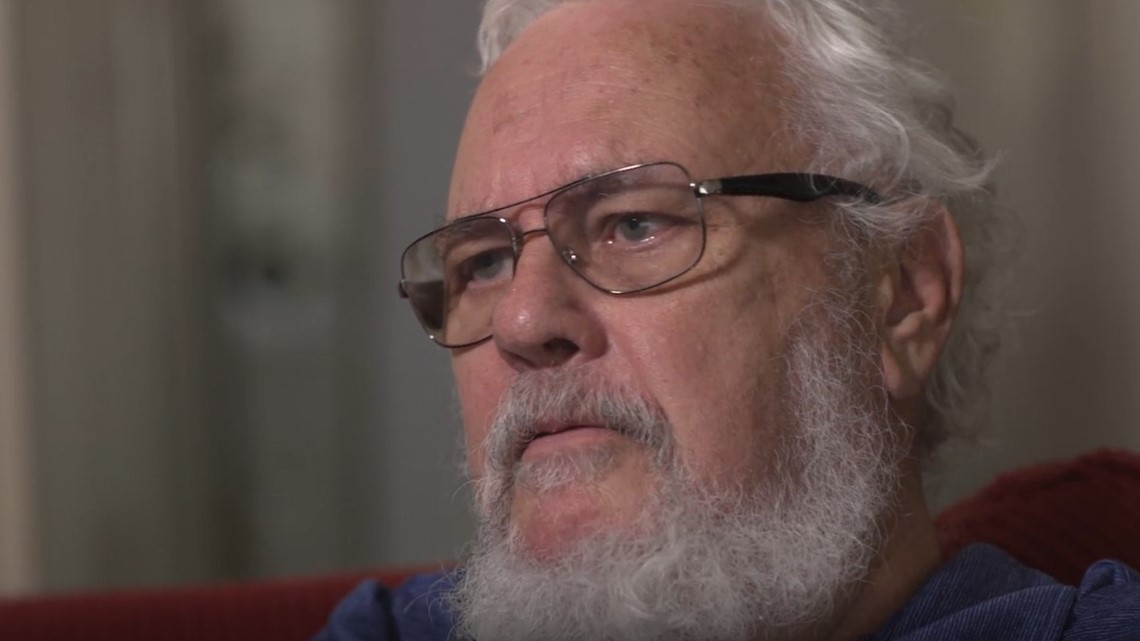

“What they’re doing isn’t right,” said former juror Ronald Repp, when asked about Sanderson Farms’ actions in the case.

Repp lives about 15 miles from Malakoff.

“Everybody was happy until the stink,” Repp said. “If the chicken farm gets shut down and it’s totally shut down,... that’ll make me happy for them.”

Chapter 7 Neighbors ask to close farm

In the end, the neighbors agreed the multi-million-dollar jury award wasn’t what they wanted. Instead, they asked that the chicken farm operation be shut down.

In ordering the farm to close, Judge McKee wrote that he had heard, among other things, “conflicting, inconsistent and concerning testimony” from Sanderson Farms’ contract growers.

The Tyler-based 12th Court of Appeals, in a 15-page ruling, upheld McKee’s decision. The appeals court concluded McKee did not overreach “because...the nuisance was of a recurring nature.”

Now, all sides await the Texas Supreme Court decision.

“Losing is not an option, because if I lose, then this whole area is going to be destroyed,” Frank Blanchard said. “I am fighting for rural Texans that I don't even know.... I'm fighting for everybody.”

Email: investigates@wfaa.com

More from WFAA Investigates: