GALVESTON, Texas — On this day 120 years ago, the "Great Galveston Hurricane" wreaked havoc on the South Texas island community.

On that fateful day, the hurricane roared ashore, devastating Galveston with winds of 130-140 miles per hour and a storm surge in excess of 15 feet.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Galveston & Texas History Center, an estimated 8,000 people died on Galveston Island due to the storm; up to several thousand more casualties were on the mainland.

The NOAA reports 3,600 buildings were destroyed and damage estimates exceeded $20 million ($700 million in today’s dollars).

To this day, the 1900 Galveston hurricane remains the deadliest natural disaster in the nation’s history, according to the NOAA.

The following information is from the NOAA's special report, "NOAA Celebrates 200 Years of Science, Service and Stewardship."

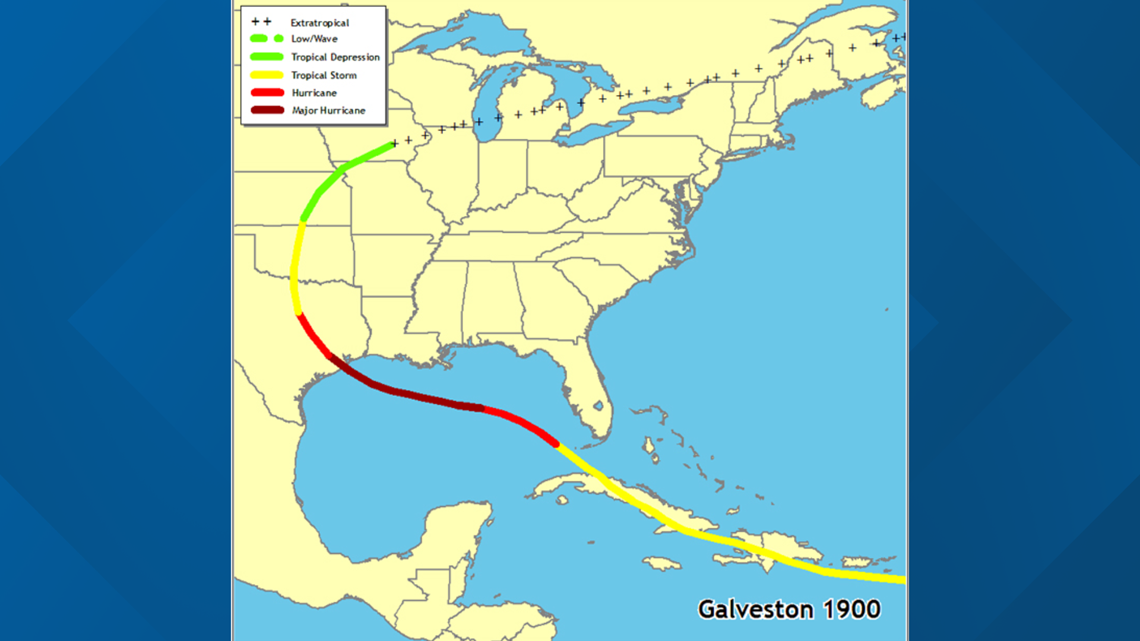

U.S. Weather Bureau forecasters were aware of the Galveston hurricane as early as August 30. By the time the storm passed over Cuba (September 4) and reached a position just northwest of Key West (September 6), forecasters were convinced the storm would continue to track to the northeast. But, once in the Gulf of Mexico, the system began to strengthen and veer westward — on a collision course with the Texas coast. Since wireless ship-to-shore communications were not yet available, there was no way to know just when and where the hurricane would strike.

While the usual signs associated with the approach of a hurricane were still not in evidence, Galveston Weather Station Chief Isaac M. Cline was becoming increasingly suspicious of the weather. On September 7, Cline ordered hurricane warning flags to be flown.

In a special report on the hurricane, published in the Monthly Weather Review, Cline later noted:

“A heavy swell from the southeast made its appearance in the Gulf of Mexico during the afternoon of the 7th. The swell continued during the night without diminishing, and the tide rose to an unusual height when it is considered that the wind was from the north and northwest…”

Early the next morning, Cline said he harnessed his horse to a cart, drove to the beach, and warned everyone of the impending danger from the storm — advising them to get to higher ground immediately. At the time, the highest point in the city was only 8.7 feet above sea level.

During the storm, Galveston was inundated with a storm surge of 15.7 feet. Cline and his brother Joseph continued to send updated reports to headquarters until the last of the telegraph lines went down.

Cline reported winds increased steadily throughout the afternoon, reaching a sustained velocity of 100 miles per hour shortly after 6 p.m. — at which time the station’s anemometer was blown away. Within another two hours, wind speeds were estimated in excess of 130 miles per hour.

With the wind and debris swirling around them, the citizens of Galveston waded through the rapidly rising floodwaters, seeking protection in the strongest-looking homes and structures they could find. One of these structures was Cline’s own house, where his wife, three daughters, brother, and about 50 neighbors took refuge from the maelstrom.

The house was a solid structure and Cline believed it might have survived the storm’s fury if a railroad trestle had not been ripped free and borne along by the wind and waves.

He recalled:

“The street railway trestle was carried squarely against the side of the house like a huge battering ram; the house creaked and was carried over in the surging waters and torn to pieces.”

Cline and his brother managed to save his three daughters, but his wife was among the thousands who died that night. Many of those who survived would carry the memories and replay the nightmare of that terrible night for the rest of their lives. A collection of survivors’ letters, memoirs, and oral histories have been archived in Galveston’s Rosenberg Library. Some of the more memorable accounts are captured in a publication entitled, “Through a Night of Horrors: Voices from the 1900 Galveston Storm.”

One of the “voices” was that of traveling salesman Charles Law, who took shelter in the city’s sturdy Tremont Hotel. Excerpts from a letter to his wife describe his ordeal:

“I have passed through the most trying, horrible thing in my life. God knows that on Saturday night I had given up all hopes of ever seeing the light of day, and my prayers were on my lips asking God to take care of you and the little darling there at home, seemed that I would be floating with the thousand poor dead bodies out in the streets at any moment.

On Sunday morning, after the storm was all over, I went out into the streets and the most horrible sights that you can ever imagine. I gazed upon dead bodies lying here and there. The houses all blown to pieces; women, men and children all walking the streets in a weak condition with bleeding heads and bodies and feet all torn to pieces with glass where they had been treading through the debris of fallen buildings. And when I got to the gulf and bay coast, I saw hundreds of houses all destroyed with dead bodies all lying in the ruins, little babies in their mothers’ arms.”

As the citizens of Galveston began to come to grips with the initial shock and horror surrounding them, they realized the most immediate task was to find a way to deal with the massive carnage.

In his memoirs, Galveston Daily News correspondent Ben Stuart offered this graphic account:

“It was determined to load the dead on barges, tow them to sea and cast them into the deep. This was done, and the gruesome spectacle then presented is one none who were witness desire to see again. Many of these bodies were again cast ashore by the currents, and it was seen that some other method must be invoked. Burial on the spot where found, or incineration, generally the latter, were the only practicable methods – and they were pursued for more than six weeks. There were huge piles of burning wreckage, in which bodies of victims were being consumed…”

At the age of 19, Galveston’s Emma Bernie Beal was one of those who bore witness to the burning — an image that would haunt her dreams for years:

“I stood out there and watched them burn some bodies. It was right across the street, on the corner of 37th and P. I recall this one body, the arm went up like that and I screamed. I never will forget that. I just saw the hand go up. I’d stand there and watch them burn the bodies and then I’d have nightmares and scream and holler. Oh, it was a terrible thing. There’s something crazy about you when you watch anything like that.”

In what has frequently been described as the city’s finest hour, the citizens of Galveston displayed exceptional resiliency and determination. They decided to rebuild and, in so doing, achieved a remarkable feat of civil engineering. The two-fold project called for raising the grade of the entire city and building a seawall to help protect it.

The first challenge was to raise all of the structures with jackscrews. Sewer and gas lines and utilities were also raised. Dikes were then built around sections of the city and sand dredged from Galveston’s ship channel was pumped through a network of pipes as liquid slurry. The water drained, the sand remained, and, within a decade, 500 city blocks had been raised with heights varying from one to up to 11 feet.

During that same period, engineers were also busy constructing the seawall. Initially, it spanned nearly 50 blocks, providing protection for the heart of the city. The seawall was tested in 1915 when a Category 3 hurricane battered the coast with sustained winds of 120 miles per hour and a 16-foot storm surge. The city sustained serious flooding and while the wall was damaged, it held up, preventing a repeat of the devastation experienced in 1900. The 1915 storm caused limited damage and only six deaths in the city of Galveston. Several hundred homes were destroyed and 42 deaths occurred in unprotected portions of the island.

Additional sections have been added to the seawall over the years. Today, the wall measures 16 feet at the base, rises 17 feet, and spans more than 10 miles of coastline. However, that still leaves two-thirds of the island, and a growing number of its residents, in harm’s way.

The ability of the National Hurricane Center, part of NOAA’s National Weather Service, to detect, predict, and warn for dangerous storms and hurricanes has improved dramatically over the years. Today, geostationary satellites provide continuous surveillance that helps determine the location, size, and intensity of developing storms. Powerful computers and sophisticated programs help provide longer, more accurate track forecasts and detailed storm surge models.

Both NOAA and the U.S. Air Force use specially equipped aircraft to fly into hurricanes to measure wind, pressure, temperature, and humidity and to pinpoint the location of a storm's core. These flights enhance scientists' understanding of hurricanes and improve forecast capabilities. As hurricanes approach coastlines, the National Weather Service’s land-based Doppler weather radar network is used by forecasters to monitor storm movement and develop inland hurricane warnings.

With all of the new developments in data-gathering technology, computer modeling, and scientists’ enhanced knowledge of the structure and behavior of tropical systems, there is virtually no possibility that a hurricane could escape detection today. Weather researchers still do not fully understand all of the facets of hurricane development, intensification, and direction. However, the tools at hand now do provide for more accurate forecasts and earlier warnings, allowing citizens enough time to protect themselves and their families and to help ensure our coastal communities are never again plagued with the level of death and destruction wreaked upon Galveston on September 8, 1900.

- Greene, C.E., & Kelly, S.H. (2000). Through a Night of Horrors: Voices From the 1900 Galveston Storm. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press

- Larson, E. (1999). Isaac’s Storm. New York, N.Y.: Crown Publishing Group

- Larson, E. (1999). Isaac’s Storm: History of Galveston. Retrieved August 21, 2006, from: http://www.randomhouse.com/features/

isaacsstorm/greatstorm/historygalveston.htm

EDITOR'S NOTE: The above information was contributed by Ron Trumbla, NOAA's National Weather Service.