LEIGH, Texas — A Dallas man with East Texas roots is on a mission to bring back a quilt made by enslaved people on a plantation just outside of Marshall that's currently housed in a British museum.

Eric Williams began his journey back to East Texas as he was researching for his film, "Finding Mirriam," a documentary that follows his enslaved ancestors in Harrison County like his great-great grandmother Mirriam Williams.

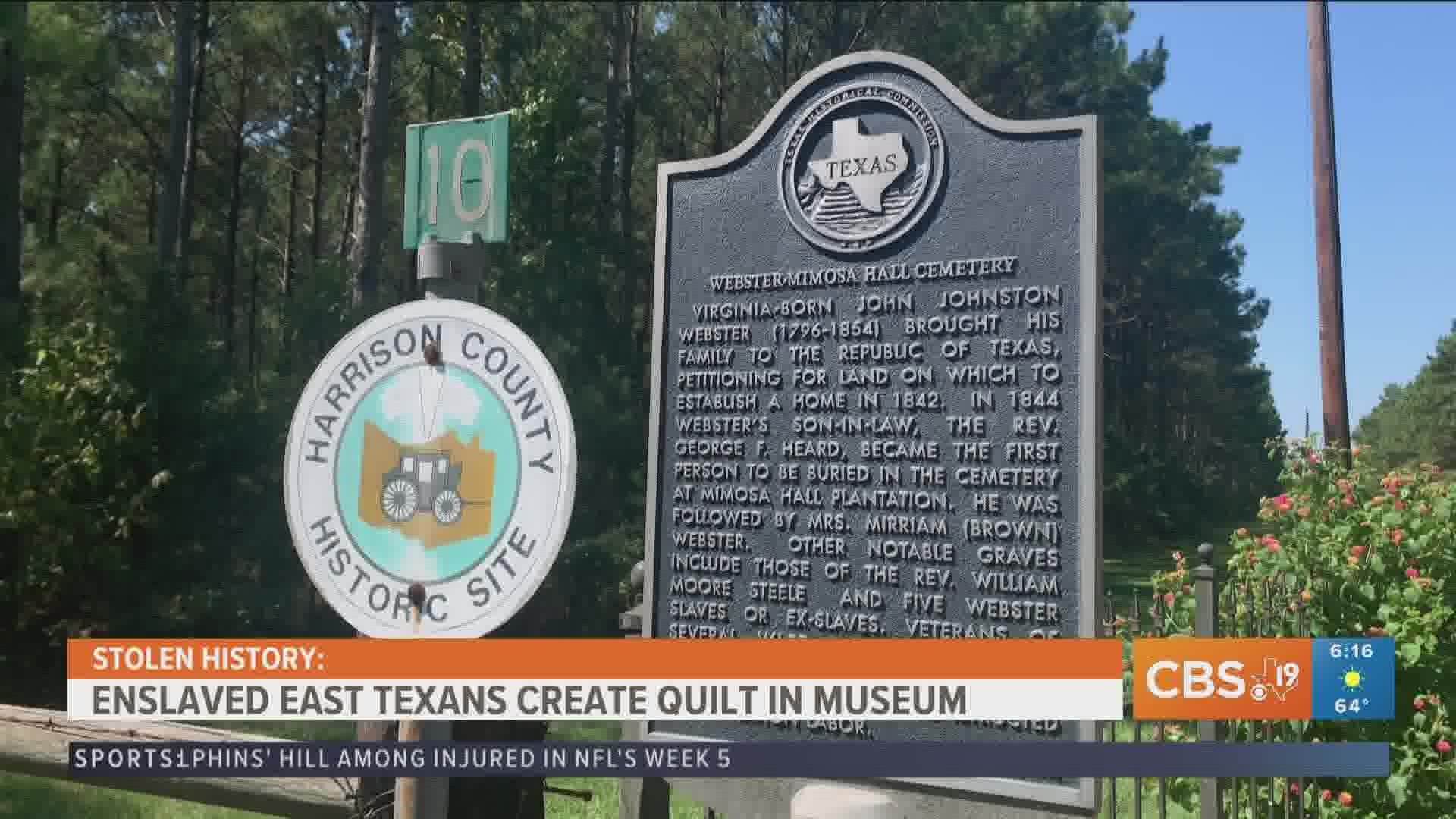

Mirriam was a part of the group that made the chalice quilt, which is currently housed in the American Museum & Gardens in the United Kingdom, while enslaved on the Mimosa Hall Plantation in the small community of Leigh. She is buried next to the slave master and his wife.

Through research, Eric Williams said he found documentation that the quilt came from Mimosa Hall and was originally made for a bishop out of New Orleans. But somehow the quilt made its way to the American Museum in Britain.

He believes the quilt was stolen from its intended destination.

"Lives were taken, livelihoods were taken, people were not compensated, never been compensated to this day," Williams said.

In late September, he sent a letter to King Charles III and the museum asking the quilt be returned so it can be placed in the Martin Luther King Jr. Museum.

He noted that the quilt is a piece of cultural heritage that was used to hide secret codes for runaway enslaved people traveling on the Underground Railroad.

"That whole entire quilt was designed as a roadmap for runaway slaves utilizing the Underground Railroad. That's a culturally significant heritage piece to all people of color," he said.

Williams said the museum has made money off of a quilt they did not manufacture for many years, and there's a need for reparations and returning the quilt.

After sending the letter, the museum officials told Williams the quilt will be taken down from online and it will no longer be sold. They did not mention if the quilt would be returned to East Texas.

"They didn't know Mirriam's spirit was going to come back years later, through me and my family, to uncover all these things can only stay covered up for so long before the dust starts to blow away," he said.

Williams added it's difficult to research the ancestry of enslaved people because they treated as property and the masters were taxed for owning slaves.

"Before 1850, we were just numbers. And we were listed right alongside the livestock. But we were taxed," he said. "They made money off us. But we didn't reap any benefits from the tax. So we didn't get a return on the taxes."