TYLER, Texas — When three-day-old cheetah cub Kubwa's mother stopped producing milk, the Wildlife Safari team in Oregon knew they had to act fast.

"Whether it's in human care or out in the wild in Africa, cheetahs won't raise a single cub," Sarah Roy, the Wildlife Safari's Carnivore Supervisor, said."The motherly instinct just isn't strong enough."

Kubwas was, after all, important to saving the cheetah species.

A cheetah at Tyler's Caldwell Zoo had a litter on Tuesday, Oct. 13 — only three days before Kubwa's birth. For Roy, it meant a possible home where Kubwa could be raised by her own kind.

"Yes, we could have kept the cub and bottle raised her," Roy said. "But she's going to lose her social skills. She's not going to grow up with siblings or parents, and that can really hinder them as adults when they get to breeding age."

But to get there in time for Kubwa to open her eyes and have the first thing she sees be her surrogate mother, they'd have to tackle a 37-hour car ride from Winston, Oregon to Tyler, Texas with one very hungry cheetah cub.

"That was rotating between sleeping, eating and bottle-feeding," Roy laughed. "As good as our formula is these days, it's no replacement for mom's milk — and the cub felt that same way. She was chirping for the last six hours. It's cute, like a bird, unless you're in a car with it."

Both Caldwell Zoo and Wildlife Safari are part of the Cheetah Sustainability Program and are one of the ten breeding facilities in North America. With less than 7,000 cheetahs left in the wild and the healthy population slowly dwindling, their mission is simple: ensure that cheetahs survive.

But that's easier said than done.

"Cheetahs are super hard to breed," Roy said. "They take a lot of expertise, space, privacy. Really just monitoring their every move and behaviors."

Both zoos are also members of the Species Survival Plan, which tracked cheetahs' genetics.

"Cheetahs are doing so poorly population-wise in the wild, and we're trying to get that turned around and protect those populations, but the genetics are just really suffering," Roy said.

Often, cheetahs fall into "genetic-bottlenecking," meaning a cheetah in captivity and one in the wild have almost no genetic variability.

That's why Kubwa is "the most important cub to be born this year." Both her parents were first time breeders, meaning her genetic line is completely unique.

Put simply her genetic line is essential to the survival of the species.

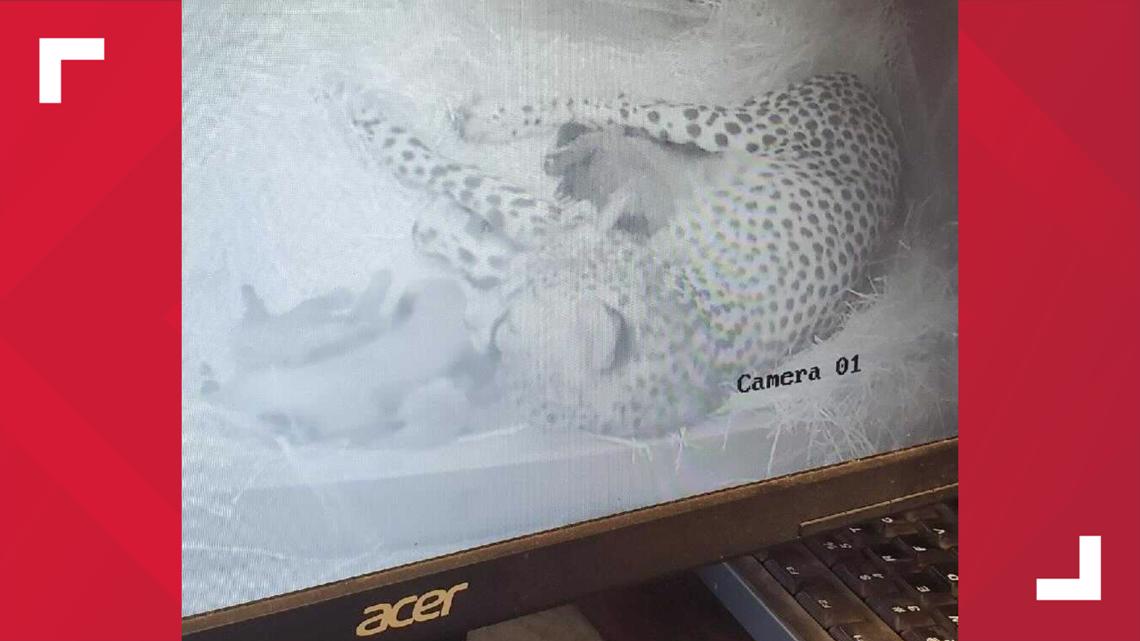

Once they arrived at Caldwell Zoo, members of Tyler's mammal team rushed to prepare their litter for its new addition.

After scrubbing Kubwa with hay in the enclosure to ensure she smelled like the rest of the litter, the two teams of zookeepers watched anxiously to see if Kubwa's new mother would accept her.

Within two minutes and after various sniffs and licks, the cheetah happily accepted Kubwa into her now litter of five.

"You're gonna know pretty instantly if it's going to go good or bad," Roy said. "For it just to go so perfect, we've been getting updates our whole drive back from the zoo and she's just been acting like that cub was hers all along. She's grooming it regularly, it's nursing with the other four cubs. It's just been the best feeling. It's these little things that make our job really worth it."