JACKSONVILLE, Texas — About 750 miles off the coast of Japan in the Pacific Ocean is the tiny volcanic island of Iwo Jima. At only eight square miles, it is more than five times smaller than Disney World. Yet during the Second World War, the 5,189 acres of Iwo Jima became one of the most important pieces of land for the Allied Forces in the Pacific.

The island had been considered Japanese for centuries before World War II. By 1943, about 1,000 people lived on the island, relying on small farming operations to sustain the population. However, the Japanese were well aware of its military significance.

The island allowed Japanese aircraft to intercept American bombers headed toward the Japanese mainland. If the Americans were to take the island, P-51 Mustang fighter planes could escort B-29 bombers all the way to the mainland and back. Iwo Jima also provided a crucial barrier between the Americans and the island of Okinawa.

By 1945, the Japanese military situation was critical. The Imperial Navy had been crippled by three years of combat. In addition to this, the Japanese fleet of planes had also been crippled, forcing the Japanese to fight a defensive war. U.S. military officials believed Iwo Jima was ripe for the taking and the battle would quickly be won.

As the Allies prepared for an invasion of Iwo Jima, Stuart McAnally, a Seabee in the United States Navy, had joined the 5th Marine Division in Hawaii and had been shipped into the war-torn Pacific.

"I got an invitation from Washington to join the Seabees. That was a new thing," McAnally remembered. "By the time I had been there a year, we had shipped out."

The Jacksonville, Texas native had been trained in Virginia to both build Navy ships and to fight the enemy. As his ship steamed out of Hawaii, McAnally realized the deadly seriousness of their mission, even if he was unaware of what exactly the mission was.

"When we boarded that ship, we realized that we may be on a one-way trip," McAnally remembered. "We would never see the land again."

Meanwhile, the Japanese were preparing for a last stand on the island. When the Americans did eventually attempt their inevitable landing, the Japanese had designed a ready-made killing field.

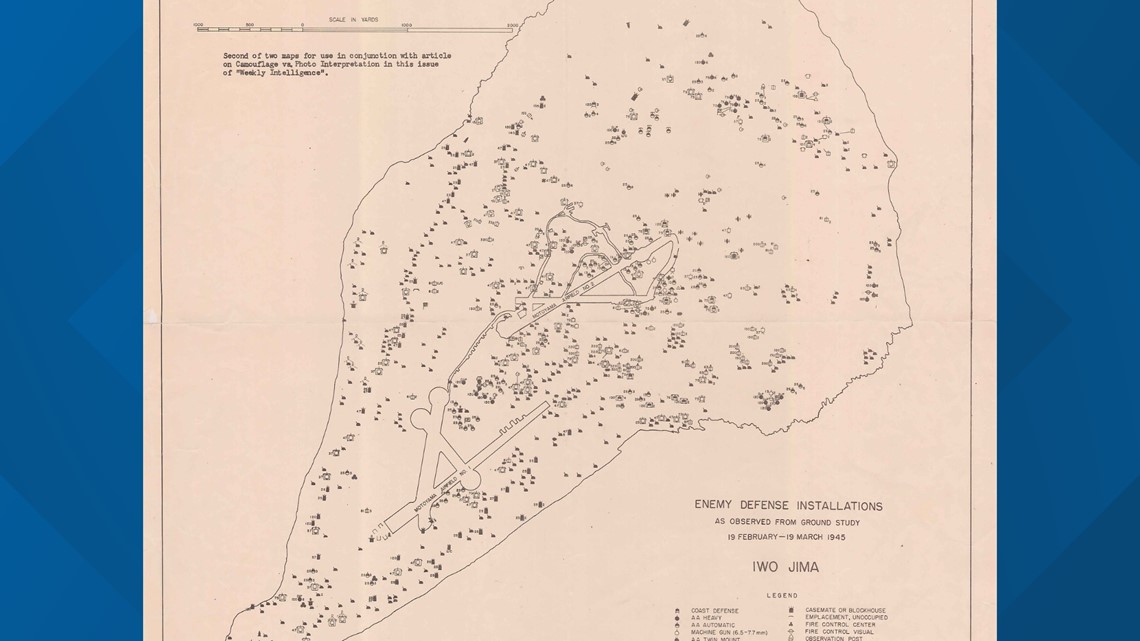

Knowing they could not match the American man power or would not receive any naval support during the battle, the Japanese chose to dig into the island. Miles of tunnels were dug, connecting pillboxes, bunkers and hidden supply depots.

Artillery was placed all over the island, most prominently on Mount Suribachi, on the island's southern tip. At 528 feet high, the highest point of the island, Suribachi offered the Japanese a perfect look over the island's landscape and a strategic point from which to fire artillery. In addition to artillery, the Japanese placed land mines, machine guns and snipers in well-camouflaged areas.

On the night of Feb. 18, 1945, McAnally's ship was off the coast of Iwo Jima as American shipped fired shells onto the small island to hopefully damage Japanese defenses for the land invasion. That night, troops were being prepared to land on the beach.

"The Seabees [weren't] even supposed to go in until they had gotten the island well under control," McAnally said. "But it didn't work out like they planned."

On Feb. 19, at 8:30 a.m., U.S. Marines began to deploy on the beach, unaware that the three-day shelling that had commenced before the attack had done little damage.

Japanese commander Tadamichi Kuribayashi quietly placed his units in position, waiting for the right moment to attack. Due the difficulty of the landing, the Americans had tightly packed the beach with men, equipment and vehicles while some units started to march inland.

However, just after 10 a.m., more than an hour after the first boat landed on the beach, the Japanese opened fire with machine guns, artillery and mortars, inflicting high casualties and waking American commanders to the sobering realization that the bombardment had little effect on the island's defenders.

"[The Japanese] were underground just waiting," McAnally said. "They were just pounding that beach with everything they had, and they couldn't miss. They were slaughtering our people."

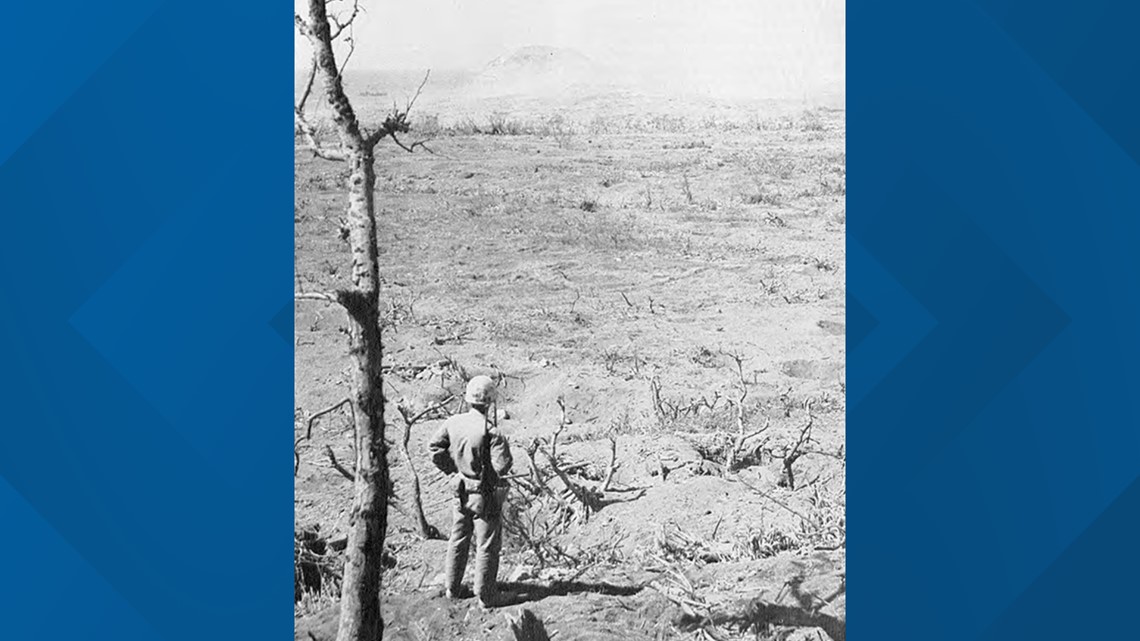

While the Americans were trying to shield themselves from the relentless Japanese fire, the Marines had trouble getting a foothold on the beach. The volcanic sand made it difficult for Americans to establish defensive foxholes or move vehicles, especially once American forces reached at crest on the beach. The mounting casualties made matters even worse.

The initial American invasion was broken into several different parts. The Army's 147th Division was ordered to engage troops on Mt. Suribachi from a ridge near the mountain. A number of Marines were to attack and attempt to take one of the two airfields on the island.

The 25th Marine Regiment attacked a strongly defended Japanese position on far, right flank of the U.S. lines. However, the Marines were forced to cross an open beach against artillery and machine gun fire. There was little cover as company after company was cut down by the relentless Japanese fire. An entire battalion was wiped out before the fighting subsided and the Marines had suffered more than 80% casualties.

Most successfully, the 28th Marines were able to capture a crucial narrow strip of land that split Japanese forces in two. By nightfall, more than 30,000 Americans had successfully deployed onto the island with tens of thousands to follow. One of them was Seabee Stuart McAnally.

On the third day, McAnally was to join the fight. Loading into a landing boat, the beach commander on his ship told the Seabees the beach was not safe for landing and told the boat to circle around until a safe landing could be made.

"We was taking on water. Our coxswain pulled up alongside the destroyer, and he said, 'We are either going in or down,'" McAnally said. "And I'll never forget what that officer on the destroyer said. He says, 'Well, hit and get the hell out!'"

As their landing craft approached the island, McAnally could hear the distinct sound of gunfire pounding against the boat. The fire was coming from Mt. Suribachi, which was still in Japanese hands.

"The ramp wouldn't let down, and we had to climb over, with them shooting at us, but [it] was a long shot, fortunately," McAnally said. "There was an old boy from West Texas, and he was shot through the neck. And he had the end of his war."

After McAnally saw his first taste of the bloody action on Iwo Jima, fear began to grip the young man.

"You go through a point of terror. You see people all around you dying, and it could be you next," McAnally said. "But finally, you just say, 'Well I'll either live or die.' And you just get numb to it and do your job."

Taking the island was an painfully slow process with the stubborn defense commanded by General Kuribayashi. The Americans had particular trouble knocking out the well-defended Japanese pillboxes and artillery. Many of the attacks on Japanese positions were made without any cover, as Japanese soldiers harassed forces with surprise attacks from the island's tunnel system.

At night, Japanese soldiers would emerge from their positions to carry out sudden and ferocious banzai attacks.

As the Americans continued to fight, the Seabees continued to work on building a road for American vehicles to advance from the unstable volcanic sand beach inland. By the end of the third day, the road was complete.

"Our [bulldozers] had a road that was right at the south end of the number one airstrip," McAnally remembered.

The battle's climax centered on the Mount Suribachi itself. With Japanese artillery position on the mountain, as well as its high vantage point to observe the battle from, the battle could not be won until the American flag flew on Suribachi's summit.

While the Americans expected a fierce fight, there were only small skirmishes with a handful of defenders on the mountain. On February 23, the fifth day of battle, a Marine platoon finally reached the summit and planted a small flag on top. Lt. Col. Chandler W. Johnson, perhaps seizing an opportunity to improve the morale of his men, ordered a second, larger flag raised. The flag was attached to a water pipe.

"I seen these guys on top of Suribachi. I knew they wasn't Japanese. I knew they [were Americans because] they was out in the open," McAnally remembered. "[That's when I saw] that flag go up. There was a many man lost trying to take [Suribachi.] All it meant to me was they would quit shooting at us. We had no idea it would become the symbol it did."

Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal captured the moment in one of the most iconic photographs in history.

However, the battle was far from over.

With Suribachi in American hands, the battle shifted to the north end of the island, where the Japanese defense remained strong with some of the best fortifications on the the island. The main objective was dubbed the "meat grinder," a heavily defensed plateau on the rocky northern part of the island toward the second airstrip.

The most ferocious fighting was at the Amphitheater, nicknamed for its unique shape between Hill 382 and Turkey knob. The Americans would launch a number of attacks on the roughest terrain of the battlefield against well-placed and determined Japanese soldiers. It was not until February 27 that the U.S. finally broke through Japanese defenses.

At about the same time, McAnally and the rest of the Seabees feverishly worked to prepare the airstrips for American use.

"[We had to] get it ready for fighter planes to land. We got that No. 1 airstrip where the crippled B-29's could land," McAnally remembered. "That was the main purpose of taking the island, I heard."

By war's end, more than 2,000 B-29 bombers would land on the island.

Finally, by March 9, the Marines had surrounded Hill 382 and Turkey Knob, showing that Japanese defeat was imminent. However, fierce fighting continued on the island, even after the Americans declared the island secure on March 16. It would not be until 10 days later, on March 26, that the battle was truly over.

The victory was one of the most crucial in the Pacific Theater of World War II, and one of the costliest. The Battle of Iwo Jima cost the American more than 26,000 men. Of that number, more than 6,000 were killed. By comparison, the Japanese suffered roughly 18,000 casualties. Among the roughly 3,000 dead was General Kuribayashi, who is thought to have died some time during the battle's final days.

The battle's importance however went beyond its location, as the lessons learned during the Japanese defense of Iwo Jima, would be applied when the U.S. attacked the more strategic island of Okinawa.

The United States awarded 27 Medals of Honor for actions during the battle, many of them posthumously. Many other soldiers received medals for their heroism during the fierce battle.

"I can turn the time back and see that little old island so plain," 96-year-old Stuart McAnally said, sitting his living room, 75 years later. "It's unbelievable."