Apollo 10: The dress rehearsal that paved the way for mankind's 'giant leap'

Before Neil Armstrong could walk on the moon on Apollo 11, the crew of Apollo 10 had to make sure the lunar module could safely land on the moon.

NASA

When Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon on July 20, 1969, it became one of the greatest technological achievement in the history of civilization. That "giant leap for mankind" was a one of the rare moments in history where Western World stood together in awe of man's accomplishment.

Comparable only to the engineering achievement of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, the Apollo 11 moon landing demonstrated the ingenuity of the United States when given the challenge.

Like the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad a century earlier, the moon landing was only the visible celebration of a decade-long struggle to conquer the unknown. Like the railroad passing through the Sierra Nevada, Apollo 10 represented the last sprint toward the ultimate prize.

So important was the mission, one could argue Apollo 10 is the most important dress rehearsal in the history of mankind.

The Space Race

"I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space..."

-President John F. Kennedy, May 25, 1961

When President Kennedy spoke those words before a joint session of Congress, the challenge captured the imaginations of Americans. It was a patriotic motivation after the failure of the Bay of Pigs days earlier.

In truth, the U.S. Space Program was in no shape to challenge the Soviets.

The Space Race had begun badly for the U.S. The Soviets beat the Americans into space with the launch of Sputnik in 1957. It was the first foreign object to reach space. Americans reacted with a mixture of awe and fear, as some Americans believed Sputnik was the next step toward nuclear war.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower famously downplayed the triumph saying, “From what [the Soviets] say, they have put one small ball in the air."

The Soviets also put the first man in space when cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited the Earth on April 12, 1961.

However, with Project Mercury, the U.S. launched Alan Sheppard into space. Later, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth.

Following that, the U.S. launched Project Gemini, which helped the U.S. take the lead in the Space Race. During Gemini, the U.S. perfected several in space maneuvers that would be vital to landing on the moon.

With the success of Mercury and Gemini, NASA launched the Apollo Program, specifically designed to put a man on the moon.

The program began with an ominous start on January 27, 1967 when a fire sparked in the command module during a training exercise.

All three crew members, Virgin “Gus” Grissom, Ed White and Roger B. Chaffee, were killed in the deadliest tragedy in NASA's history until the Challenger disaster nearly two decades later.

In late 1968, Apollo 8 astronauts, Frank Borman, James “Jim” Lovell and William Anders, became the first humans to leave Earth’s orbit and fly to the moon. The historic mission came as the country celebrated Christmas.

During a Christmas Eve television broadcast from their spacecraft, the crew read from the Book of Genesis. Commander Frank Borman closed the broadcast saying, "And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas and God bless all of you—all of you on the good Earth."

On December 27, 1968, the command module splashed down in Pacific Ocean, having pushed further into the final frontier than mankind had ever gone before.

Now that three Americans had made it to the moon's orbit, Apollo 9 would be the first rehearsal for the moon landing. But the mission only included Lunar Module testing while in Earth’s orbit. It never traveled to the moon.

The next mission, Apollo 10, would be NASA's only full-dress rehearsal for the moon landing in the lunar orbit.

Leading up to launch

By May of 1969, the triumph of Apollo 8 had faded. The war waging in Vietnam had deeply divided the country and had taken attention away from the Space Program.

The Battle of Hamburger Hill fought that month cost more than 600 American lives. The images of war shown on evening newscasts shocked Americans on the home front and calls to end the war in Vietnam grew louder.

Against this background, Apollo 10 was scheduled to launch from Cape Canaveral on May 18 with the most experienced three-man crew so far in the Apollo program.

The commander was 38-year-old Thomas Stafford, who became a test pilot in 1958 before entering the astronaut core. He flew on two missions for Project Gemini in 1965 and 1966.

Eugene Cernan, 35, was the lunar module pilot. Cernan had previously flown with Stafford during the Gemini 9 mission and was one of the first Americans to attempt extra-vehicular activity while in space.

John Young, 38, was the command module pilot. His claim to fame came during his mission on Gemini 3, when he smuggled a corned beef sandwich onto the space craft, which resulted in reprimands from NASA and Congress.

The call signs of the vehicles used in the mission were famously named after characters from the popular comic strip Peanuts, as a way to interest children in the space program. The Command Module (CM) was named Charlie Brown while the Lunar Module (LM) was named Snoopy. On the side of the LM, the famous aviator goggles on Snoopy had been changed to a space helmet.

Despite the rather light-hearted tone of the call signs, the mission’s importance was no joking matter. The actual mission was to test the lunar module in moon’s orbit, a much different environment than that of the earth’s orbit tested on Apollo 9.

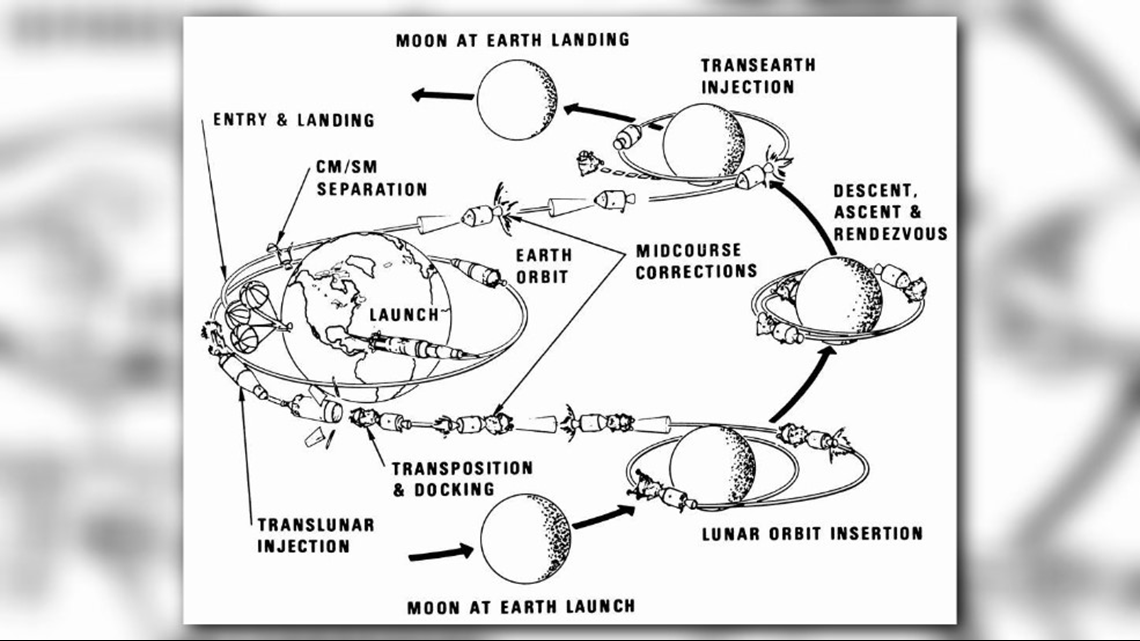

The simulation included the LM's separation from the command module, descent and ascent maneuvers, docking with the command module again and a safe jettison of the lunar module. The mission would also scope out the proposed landing site in the Sea of Tranquility named Apollo Landing Site 2.

If the mission was accomplished, NASA would be able to designate Apollo 11 as the mission in which man would walk on the moon. If it failed, the best case scenario would be the moon landing would be pushed back for months or longer. At worst, the astronauts lives would be in danger and the U.S. would have to seriously reassess the direction of the Apollo program.

The Mission

May 18, 1969 was warm, humid and windy around the launchpad. Clouds coated the overcast sky. That morning, the crew put on their spacesuits and walked toward the Saturn V rocket sitting at the launchpad. During that walk, they stopped to pet a stuffed Snoopy, a reference to the lunar module's call sign, for luck.

Once at the launch pad, the crew entered an elevator that would take them to the command module at the top of the rocket.

It took about 30 seconds to reach the top of the 320-foot launch tower.

"We could see clearly through the wide openings of the safety door. Every inch of the way the rocket beside us hummed and vibrated. Glass-like chunks of ice slid away as her cryogenic lifeblood," Cernan recalled in his autobiography. "She's alive!"

Designed in Huntsville Alabama and assembled on-site at the Vertical Assembly Center at the NASA Launch Operation Center at Cape Canaveral, the Saturn V remains the most powerful vehicle ever made. It produced 7.6 million pounds of liftoff thrust and could carry more than 260,000 pounds of payload.

The Saturn V remains the only manned rocket to ever leave the lower earth orbit.

“You can hear yourself breathe inside the suit,” Cernan told the Guardian in 2016. “Everything intensifies – but the clock keeps going.”

At 12:49 p.m. local time, the Saturn V rocket carrying the command module, service module, lunar module and the astronauts ignited and shot towards the sky.

As the ship escaped the atmosphere, Stafford realized something was wrong.

"We started climbing out in space, but as we neared the end of the burn, the whole thing started to really shake and rattle," Stafford remembered. "I had the abort handle here [in front of me]. I figured, you know, 'Hell, we were up around 31,000 feet per second.' I said, 'I've gone this far. If it blows, it blows.'"

Fortunately, the rocket made safely into Earth's orbit. Three hours after launch, the crew began their first live broadcast in color television, something that had never been done before.

"We put them on board about a week before launch," Stafford later said in an interview with NASA. "The first time you ever saw color TV from space was when we did that on Apollo 10. We had more prime time on Apollo 10 than we did on 11 or any of the others."

The broadcast showed not only the interior of the CM, but also the crucial docking of the LM.

The docking process, known as “transposition, docking and extraction,” was a complicated process on which the entire mission hinged. If not done correctly, the LM would be damaged and the mission would be a failure.

The command module and service module would be separated from the larger space craft. Then the command module pilot, John Young in the case of Apollo 10, would need to turn the CM around and dock its nose to the LM. Once the docking was completed, the LM would be extracted from the larger space craft and fly to the moon.

The CM was separated at precisely 3 hours, 2 minutes and 42 seconds into the flight.

NASA used the time into the mission, beginning at launch, to mark specific events during a mission. This would be measured by hours (measured in three digits), minutes, and seconds to the tenth second. So, the time registered in the log for separation was 003:02:42.4.

Barely 15 minutes later, the CM successfully docked with the LM. At mark 003:56:25.7, following procedures to connect the two vehicles, the LM was ejected.

Much of the process was shown live on television for the first time. Afterwards, at more than 25,000 mph, Apollo 10 escaped the Earth's orbit with their destination more than 200,000 miles away.

"We were told that because of the trajectory we would fly, we would not see the Moon until we got there. And that's kind of weird, looking around. You see the Earth go by every twenty minutes, see the Sun go by. Where in the hell is the Moon?" Stafford said.

History's Most Important Dress Rehearsal

After 73 hours, 22 minutes and 29 seconds, Apollo 10 entered began to orbit around the moon.

Nearly eight hours later, the crew performed a televised broadcast over the surface of the moon.

"Here comes the Moon, right out in daylight. So it was a real funny feeling there. It really looked weird," Stafford said. "I made the maneuver and then pitched around for the attitude, got the TV on and everything, and here comes the Earth up. We showed that on TV, what an Earthrise was."

Once again, it would be the first broadcast of the moon in color. Much of the broadcast featured the crew describing the features of the moon below. While grainy by today's standards, nothing like it had ever been seen before. NASA would comment the quality of the picture as "excellent."

At 095:02, Stafford and Cernan began to activate the LM for the rehearsal. However, as they prepared to launch the LM, the astronauts found the LM had moved 3.5 degrees out of line with the CM. The crew believed the misalignment could prevent redocking, leaving the two men unable to get back into the CM and back to Earth.

"You had these three latches on the end of a drogue that ran into a metal thing called a probe, and we had more failures of those in tests," Stafford said. "So if there's any weak link, it's getting back together on a rendezvous."

NASA engineers at Mission Control in Houston assured the crew if the misalignment was under six degrees, there would be no issue with redocking.

Despite their initial fears, the astronauts moved forward with the mission.

At 098:29:20, the LM separated from the CM. During this period, Stafford and Cernan began testing the LM’s systems and landing gear before the critical decent toward the moon. Meanwhile, both space crafts ran cameras to capture images from the moon.

The descent would determine how the vehicle would react within the moon’s atmosphere and to see how safely it could land on the surface of the moon. In a very real sense, the future of the Apollo program hung in the balance.

During descent, the LM began to roll unexpectedly and uncontrollably. Quickly, the crew figured out they accidentally duplicated one of the procedures, causing the roll.

"BOOM! The whole damned spacecraft started to tumble and tried to rotate like that," Stafford remembered. "And real fast, I just reached over and just blew off the descent stage, because all the thrusters were on the ascent stage."

Stafford hurriedly took control of the LM manually, preventing it from crashing onto the moon's surface.

"During that period of time we forgot we were on hot mic, and Apollo 10 became X-rated," Stafford said.

The LM continued its descent to 7.8 nautical miles (47,400 feet) above the surface of the moon. By comparison, the U-2 spy plane used by the U.S. in the 1960’s, could fly at an altitude of 70,000 feet. Most modern commercial jet liners’ cruising altitude is about 35,000 feet. It was as close to the moon’s surface as any ship had gotten up to that point.

During a low pass over Apollo Landing Site 2, the astronauts tested the landing radar, lunar lighting and different maneuvers of the descent engines.

After about eight hours, the LM began its ascent towards CM. It docked with the CM at 54.7 nautical miles above the Earth’s surface.

When the two ships met, Young famously exclaimed, "Snoopy and Charlie Brown are hugging each other!"

With Stafford and Cernan safely back in the CM, the crew jettisoned the LM and sent it out into the space in a solar orbit.

The dress rehearsal was a success.

Splashdown and the Road to Apollo 11

Beginning at 137:39:13.7, the crew began their trip back to earth at a velocity of 8,987.2 feet per second or more than 6,100 miles per hour. After the jettison of the command module, the CM reentered the Earth’s atmosphere at 191:48:54.5.

On May 26, just before 1 p.m. on the East Coast, the CM splashed down in the Pacific Ocean. The duration from launch to splashdown was 192:03:23, more than eight days.

It took less than hour for the three astronauts to be recovered on the U.S.S. Princeton.

Apollo 10 accomplished its primary missions in testing the systems and procedures of a lunar landing. NASA concluded that the vehicles, particularly the LM, could successfully execute separation from CM, the lunar landing and redocking within the moon's atmosphere.

In addition, Mission Control could handle communications between the two vehicles during critical moments of the mission.

NASA concluded that following the Apollo 10's success, Apollo 11 would be designated as the mission that would fulfill President Kennedy's challenge eight years earlier.

"I keep telling Neil [A.] Armstrong that we painted that white line in the sky all the way to the Moon down to 47,000 feet so he wouldn't get lost," Cernan said. "And all he had to do was land."

On July 16, 1969, the world witnessed Neil Armstrong land the lunar module with Buzz Aldrin and become the first man to step foot on the moon.

"I'm glad Neil and Buzz got to do it first," Young said years later. "For one thing, people would've tried to make a big wheel out of me. And another thing is, I would've never been able to fly the Shuttle. So I'm glad it wasn't me."

The Legacy of Apollo 10

In the passing years, Apollo 10’s story has been largely forgotten, overshadowed by the tragedy of Apollo 1, the success of Apollo 8, the realization of the moon's landing with Apollo 11 and the drama of Apollo 13 less than year later.

However, Apollo 10 has its unique place in the story of the Apollo Program.

During their return from the moon, the crew reached a speed of 24,791 miles per hour or 36,360 feet per second. It is the fasted verified speed any manned vehicle has ever traveled. When it reached the far side of the moon, Stafford and Cernan set the record for the farthest distance any two humans traveled from Earth.

Another footnote to the mission was supposedly mysterious music heard by the astronauts during the LM’s time orbiting the moon. At 100:13:02, Cernan reported the noise to Stafford.

“That music even sounds outer-spacy, doesn't it? You hear that? That whistling sound?” Cernan said.

“Did you hear that whistling sound too?” Stafford said.

“Yes. Sounds like – you known, outer-space-type music,” Cernan said.

The astronauts did not make much of the noise and went on with their work. It was mentioned again with Young, who also claimed to hear the noise. However, the crew agreed not to concern themselves with the noise.

According to the Smithsonian Magazine, the noise was likely radio interference. Cernan himself later commented the astronauts did not think twice about the noise.

Also noteworthy is NASA’s response to the Peanuts-themed call signs. Following the mission, NASA required astronauts to choose more formal names for their spacecraft. However, the order was rarely enforced, as the CM for Apollo 16 was named Casper, after Casper the Friendly Ghost.

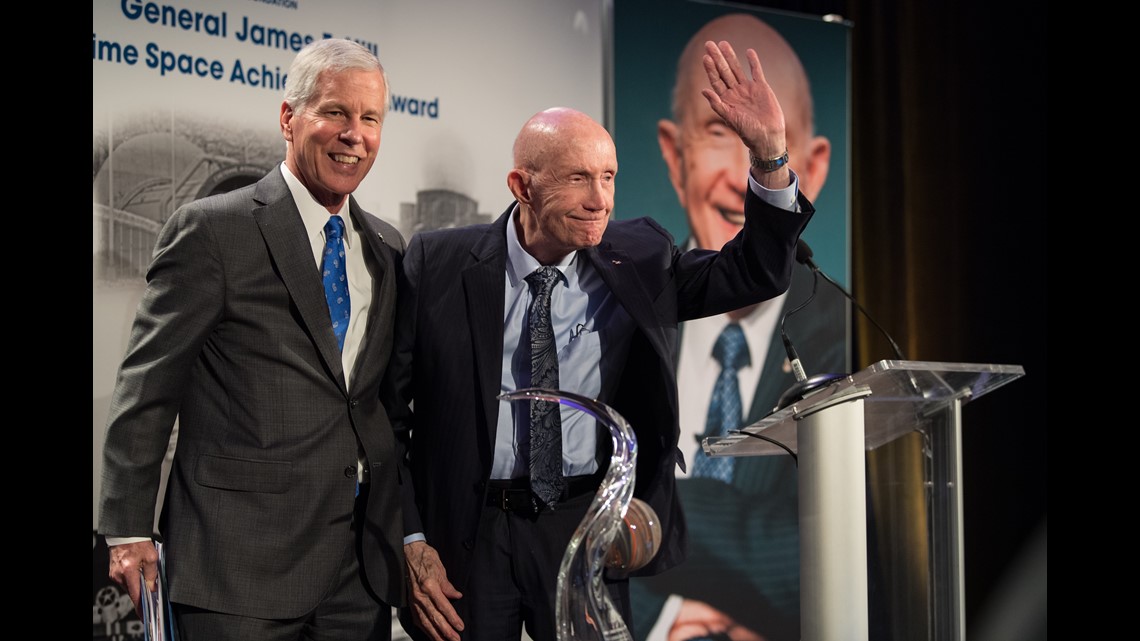

Stafford, Cernan and Young would all fly again, becoming the only 3-man crew where each crew member would fly on another Apollo mission.

In July of 1969, Thomas Stafford accepted a position as Chief of the Astronaut Office, overseeing astronaut assignments until the end of Apollo 14. In July of 1975, Stafford was commander of the U.S. side of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, linking an American and Soviet spacecraft in space for the first time.

He was promoted to Lt. General, a rank held by the likes of George Washington, Ulysses S. Grant and George Patton. Only three other astronauts achieved that ranking.

Stafford assumed command of the Air Force Flight Test Center in November of 1975 before retiring in 1979. Stafford continued to be a consultant for several years while living at his home in Oklahoma.

During his eight hours in the command module while the other astronauts were in the lunar module, John Young became the first person to fly solo in the moon's orbit.

Young remained in the Apollo astronaut program following his return from Apollo 10. In April of 1972, he served as commander of Apollo 16, becoming the ninth person to walk on the surface of the moon.

"The moon is a very nice place," Young said.

Young later said he had two vivid memories of what he discovered about being on the moon. One was the eerie silence of the vacuum of space. Second was the taste of their potassium-lace orange juice.

"I haven't eaten this much citrus fruit in 20 years," Young told lunar module pilot Charlie Duke. "But I'll tell you one thing, in another 12 (expletive) days, I ain't ever eatin' anymore."

In 1981, Young commanded the Space Shuttle Columbia on its maiden orbital flight. Two years later, he commanded Columbia again, carrying the first Spacelab module. He is the only person to fly on Gemini, Apollo and Space Shuttle missions.

Young continued to work for NASA until December 31, 2004, when he retired at 74. He lived in El Lago, Texas until his death on January 5, 2018.

Gene Cernan turned down the opportunity to be the lunar module pilot of Apollo 16 in favor for the opportunity to command Apollo 17, the last lunar mission, in December of 1972.

"I'd come close in Apollo 10, and now I was actually on the Moon, now I was actually going to step on the surface of the Moon," Cernan said. "Once my footsteps were on the surface of the Moon, nobody, but nobody, could ever take, and to this day can take those footsteps away from me."

The flight set a number of records including the longest time spent on the moon. more than 22 hours. On the lunar rover, Cernan set the unofficial lunar land speed record: 11.2 mph.

In 1976, Cernan retired from the Navy and NASA and went into the private sector. However, Cernan would provide commentary for television audiences across the country during the early Space Shuttle flights.

He spent much of his life continuing to advocate further exploration of space.

He died on January 16, 2017 at 82 in Houston.

Nearly half a century later, Cernan remains the last man to step foot on the moon.

As he prepared to the leave the surface moon's surface, Cernan reflected on the impact of the Apollo Program while looking toward the future of manned spaceflight:

“As I take man's last step from the surface, back home for some time to come – but we believe not too long into the future – I'd like to just (say) what I believe history will record: that America's challenge of today has forged man's destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus–Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind.”